88 Heroes composer Mike Clark explains how music and sound intertwine to create atmospheric game worlds in this excerpt from Wireframe issue 8, available now.

Music for video games is often underappreciated. When I first started writing music in my bedroom, it took me a while to realise how much I was influenced by the worlds that came from my tiny CRT TV. A couple of years ago, I was lucky enough to be approached by Bitmap Bureau, an indie startup who hired me to compose the music for their first game, 88 Heroes.

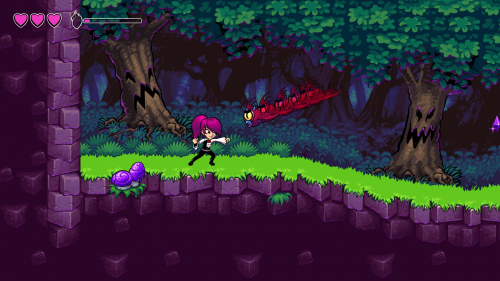

88 Heroes is a platformer styled like a Saturday morning cartoon. Interestingly, cartoon soundtracks have a lot in common with those for stage productions: short musical cues accompany the actions on screen, so if someone violently falls downstairs, you hear a piano rolling down the keys. This is called ‘mickey mousing’ in cartoons, but we hear similar things in film soundtracks.

Take Raiders of the Lost Ark, scored by John Williams: for every heroic rope swing, leap of faith, or close encounter with danger, the main theme can be heard powering through the dissonances and changing rhythms. It fills the audience with hope and becomes synonymous with the lead character – we want to see him succeed. Let’s not forget the title theme. Every time you see the Star Wars logo, does that grand title theme play in your head? It’s the same with video games. The challenge here, of course, is that players often leave the title screen after three seconds.

Three seconds is all you need though. Take Super Mario World’s soundtrack, composed by Koji Kondo. Many of its levels have the same leading melody, which changes subtly in tonality and rhythm to create the appropriate mood. The most repeating part of the melody is four bars long, but we hear it in so many forms that we only need the first two bars to know where it’s from. In classical music, this is called ‘variations on a theme’. In video games, we call it a ‘sonic identity’.

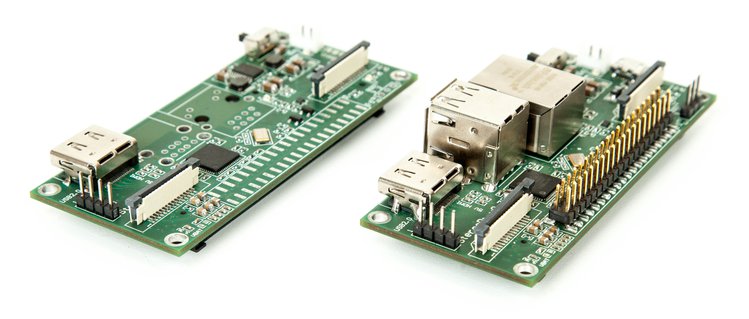

Action platformer 88 Heroes, featuring music by Mike Clark.

How a picture should ‘sound’

Sonic identity informed my approach to the 88 Heroes soundtrack. The title screen tells us that an unknown group is going to save the day. I first thought about unlikely heroes who end up on an adventure, and Back to the Future, scored by Alan Silvestri, sprang to mind. The second inspiration came from traditional superheroes, like Superman. I composed a melody which travels between the first and fifth notes in the scale (in this case C and G), with little flourishes of the notes in-between. It’s a triumphant, heroic melody.

This concept helps to connect these worlds beyond their visuals. It took a long time for games to evolve into the cohesive open-world sandboxes or MMOs we see today; the technology that masked loading screens to create a seamless experience was unheard of in the 1990s, so a melody that you hear in different ‘costumes’ gives these games a sense of cohesion.

Intelligent instruments

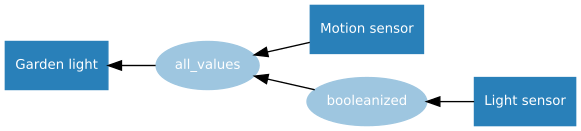

What if you have levels (or worlds) so big that some areas need to be loaded? That’s where non-linear composition comes in. Banjo-Kazooie, released for the N64 in 1998, was among the first 3D games to feature dynamic music. It used a technique called MIDI channel fading. MIDI stands for Musical Instrument Digital Interface; think of it as a universal language for music that is played back in real time by the hardware. As you walk into caves, fly in the sky, or move near certain characters, instruments fade in and out using the different MIDI channels to mimic the atmosphere, give the player an audio cue, and build and release tension.

Learning how to write music that changes as you play might seem impossible at first, but it becomes second nature once you understand the relationship between every instrument in your composition. Many digital audio workstations, like Logic and FL Studio, let you import MIDI data for a song (so you have all the notes in front of you) and set the instruments yourself. Try slowly fading out or muting certain tracks altogether, and listen to how the mood changes. What could this change represent in a video game? It’s like when you’re riding Yoshi in many of the Mario games; the fast bongos come in to represent the quick-footed dinosaur as he dashes at high speeds.

Undertale’s soundtrack blends analogue synth instruments with a plethora of real instruments to help create emotion.

Music is used to evoke emotions that wouldn’t be possible with visuals alone. Beep: A Documentary History of Game Sound shows a six-second video of a boat accompanied by two soundtracks; one is a light and happy guitar piece, the other a grating, scary, orchestral dissonance. Through these two extremes, the music creates the mood by itself. I remember playing Metroid Prime and finding the Chozo Ghost enemies rather scary, not because of their appearance, but because of the unnerving music that accompanies them. Music and sound design are one and the same. Think about what feelings you can create by taking music away entirely — it’s a great way to create tension before a boss battle or pivotal plot point, and it really works. In Undertale, scored by Toby Fox, there are times when the music stops so abruptly during NPC dialogue that you feel shivers down your spine.

So, what if you’re trying to come up with some game music, and you have writer’s block? Well, the next time you play a new game, turn the sound off. As you’re playing, focus on how the story, art, or characters make you feel, and focus on the emotions the game is trying to convey. Then, think of a time when a song made you feel happy, sad, joyful, anxious, or even frightened. Maybe you can use the music to create the mood you want for that game, as opposed to what the game makes you feel. By finding these emotions and understanding how they can change, you’ll be able to write a score that helps strengthen the immersion, escapism, and player investment in your game.

You can read the rest of the feature in Wireframe issue 8, available now in Tesco, WHSmith, and all good independent UK newsagents.

Or you can buy Wireframe directly from us – worldwide delivery is available. And if you’d like to own a handy digital version of the magazine, you can also download a free PDF.

Markets, moggies, and making in Wireframe issue 8

Make sure to follow Wireframe on Twitter and Facebook for updates and exclusives, and for subcriptions, visit the Wireframe website to save 49% compared to newsstand pricing!

The post How musical game worlds are made | Wireframe #8 appeared first on Raspberry Pi.

Source: Raspberry Pi – How musical game worlds are made | Wireframe #8