If you have one of our official cases, keyboards or mice, or if you’ve visited the Raspberry Pi Store in Cambridge, UK, then you know the work of Kinneir Dufort. Their design has become a part of our brand that’s recognised the world over. Here’s an account from the team there of their work with us.

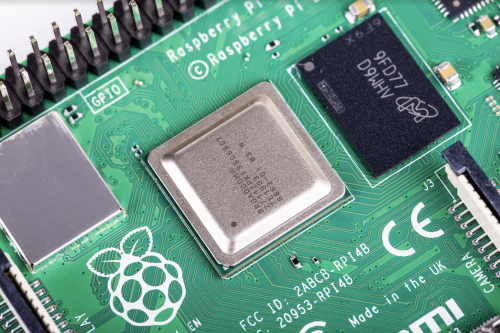

Over the last six years, our team at Kinneir Dufort have been privileged to support Raspberry Pi in the design and development of many of their products and accessories. 2019 has been another landmark year in the incredible Raspberry Pi story, with the opening of the Raspberry Pi store in February, the launch of the official keyboard and mouse in April, followed by the launch of Raspberry Pi 4 in June.

We first met Eben, Gordon and James in 2013 when we were invited to propose design concepts for an official case for Raspberry Pi Model B. For the KD team, this represented a tremendously exciting opportunity: here was an organisation with a clear purpose, who had already started making waves in the computing and education market, and who saw how design could be a potent ingredient in the presentation and communication of the Raspberry Pi proposition.

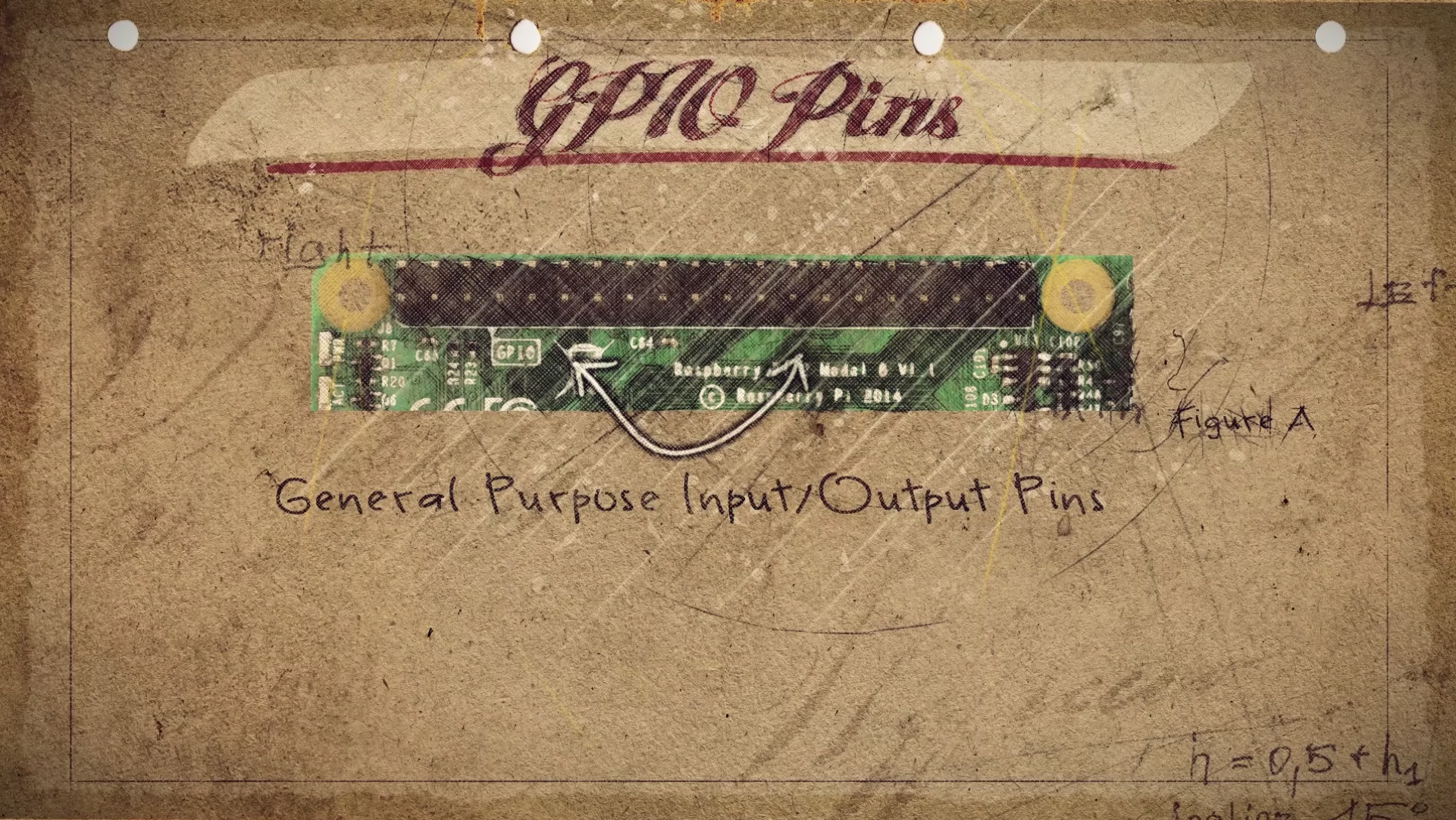

Alongside specific design requirements for the Model B case, the early design work also considered the more holistic view of what the 3D design language of Raspberry Pi should be. Working closely with the team, we started to define some key design principles which have remained as foundations for all the products since:

- Visibility of the board as the “hero” of the product

- Accessibility to the board, quickly and simply, without tools

- Adaptability for different uses, including encouragement to “hack” the case

- Value expressed through low cost and high quality

- Simplicity of form and detailing

- Boldness to be unique and distinctively “Raspberry Pi”

Whilst maintaining a core of consistency in the product look and feel, these principles have been applied with different emphases to suit each product’s needs and functions. The Zero case, which started as a provocative “shall we do this?” sketch visual sent to the team by our Senior Designer John Cowan-Hughes after the original case had started to deliver a return on investment, was all about maximum simplicity combined with adaptability via its interchangeable lids.

The ‘levitating lid’ version of the Zero case is not yet publically available

Later, with the 3A+ case, we started with the two-part case simplicity of the Zero case and applied careful detailing to ensure that we could accommodate access to all the connectors without overcomplicating the injection mould tooling. On Raspberry Pi 4, we retained the two-part simplicity in the case, but introduced new details, such as the gloss chamfer around the edge of the case, and additional material thickness and weight to enhance the quality and value for use with Raspberry Pi’s flagship product.

After the success of the KD design work on Raspberry Pi cases, the KD team were asked to develop the official keyboard and mouse. Working closely with the Raspberry Pi team, we explored the potential for adding unique features but, rightly, chose to do the simple things well and to use design to help deliver the quality, value and distinctiveness now integrally associated with Raspberry Pi products. This consistency of visual language, when combined with the Raspberry Pi 4 and its case, has seen the creation of a Raspberry Pi as a new type of deconstructed desktop computer which, in line with Raspberry Pi’s mission, changes the way we think about, and engage with, computers.

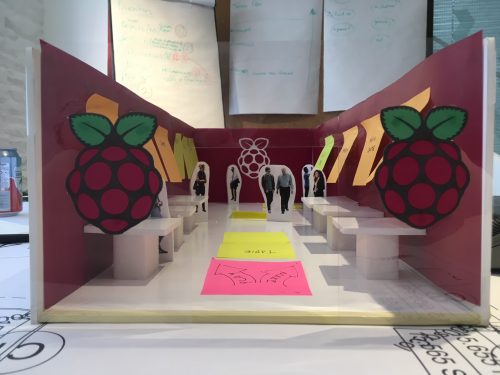

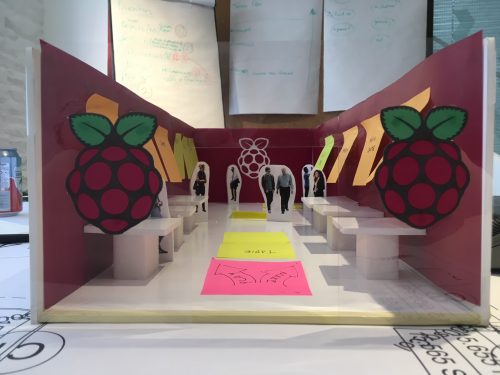

The launch of the Cambridge store in February – another bold Raspberry Pi move which we were also delighted to support in the early planning and design stages – provides a comprehensive view of how all the design elements work together to support the communication of the Raspberry Pi message. Great credit should go to the in-house Raspberry Pi design team for their work in the development and implementation of the visual language of the brand, so beautifully evident in the store.

An early sketch model of the Raspberry Pi Store

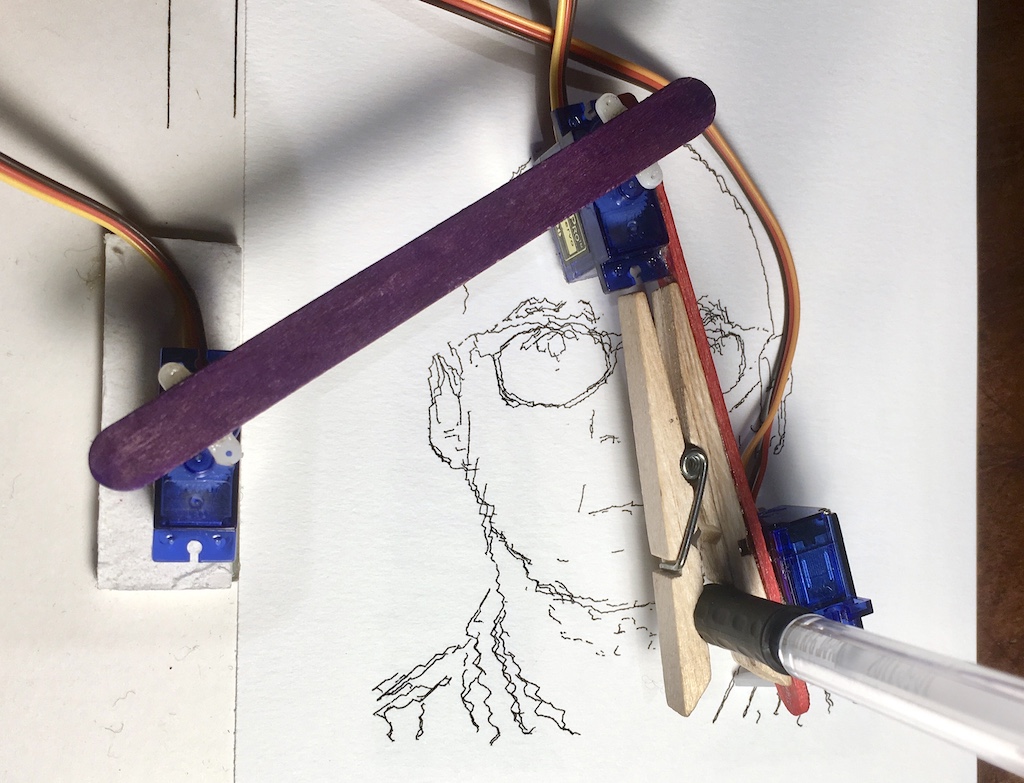

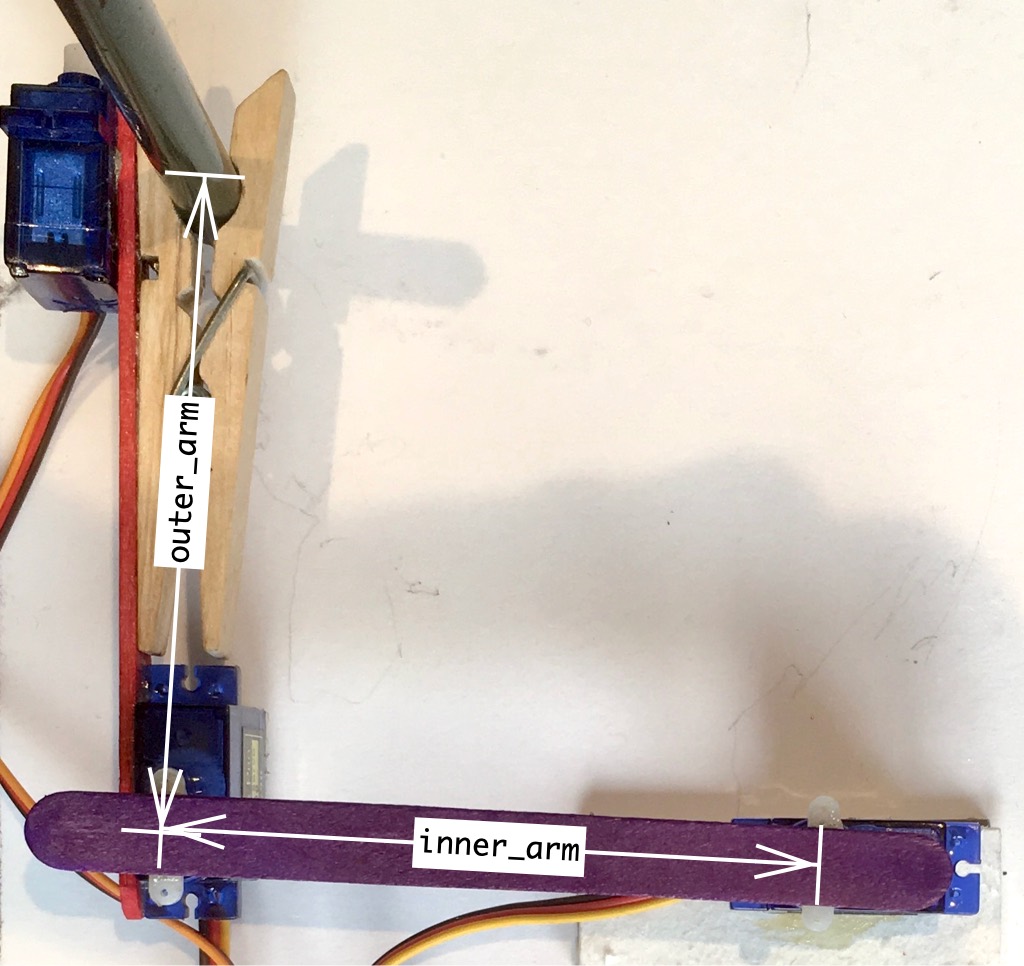

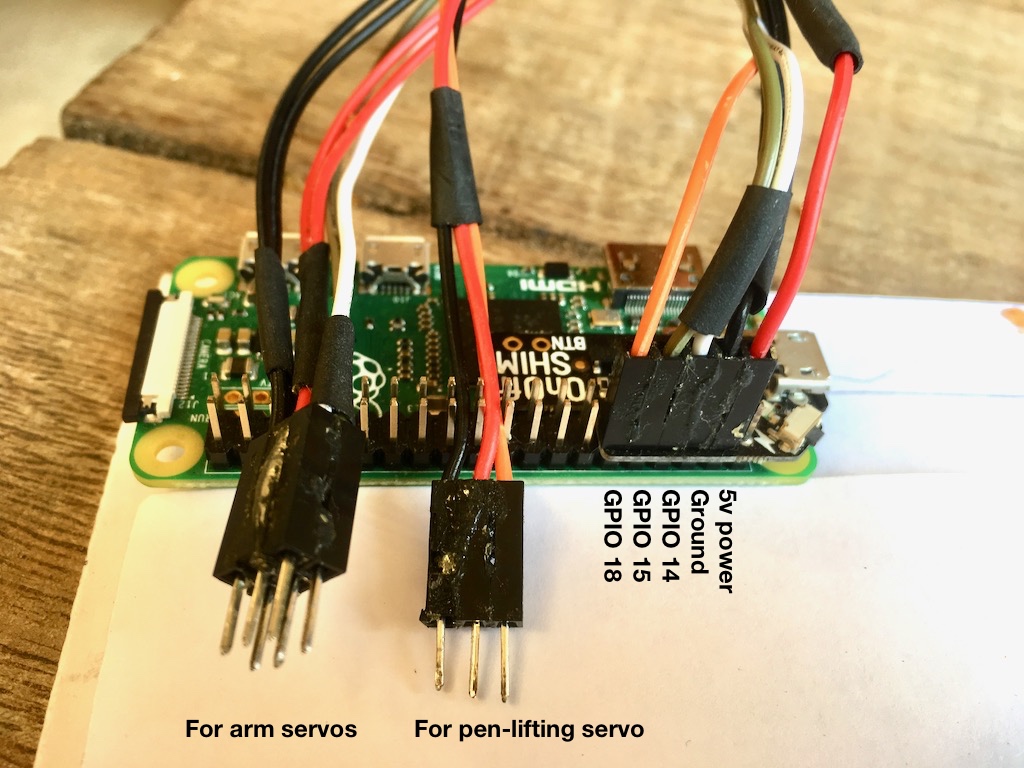

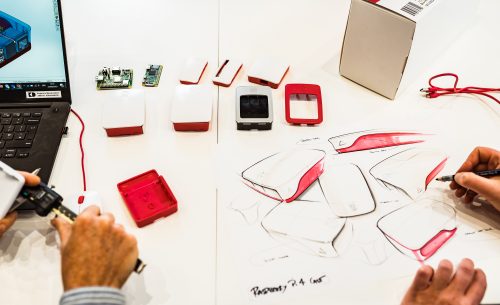

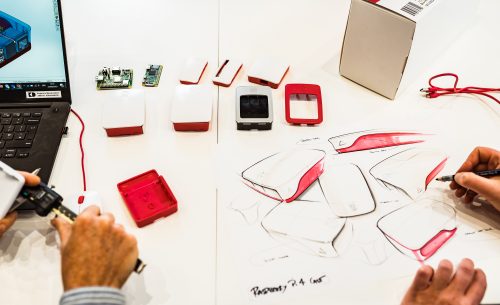

In terms of process, at KD we start with a brief – typically discussed verbally with the Raspberry Pi team – which we translate into key objectives and required features. From there, we generally start to explore ideas with sketches and basic mock-ups, progressively reviewing, testing and iterating the concepts.

Sketching and modelling and reviewing

For evaluating designs for products such as the cases, keyboard and mouse, we make considerable use of our in-house 3D printing resources and prototyping team. These often provide a great opportunity for the Raspberry Pi team to get hands on with the design – most notably when Eben took a hacksaw to one of our lovingly prepared 3D-printed prototypes!

EBEN YOUR FINGERS

Sometimes, despite hours of reviewing sketches and drawings, and decades of experience, it’s not until you get hands-on with the design that you can see further improvements, or you suddenly spot a new approach – what if we do this? And that’s the great thing about how our two teams work together: always seeking to share and exchange ideas, ultimately to produce better products.

There’s no substitute for getting hands-on

Back to the prototype! Once the prototype design is agreed, we work with 3D CAD tools and progress the design towards a manufacturable solution, collaborating closely with injection moulding manufacturing partners T-Zero to optimise the design for production efficiency and quality of detailing.

One important aspect that underpins all our design work is that we always start with consideration for the people we are designing for – whether that’s a home user setting up a media centre, an IT professional using Raspberry Pi as a web server, a group of schoolchildren building a weather station, or a parent looking to encourage their kid to code.

Engagement with the informed, proactive and enthusiastic online Raspberry Pi community is a tremendous asset. The instant feedback, comments, ideas and scrutiny posted on Raspberry Pi forums is powerful and healthy; we listen and learn from this, taking the insight we gain into each new product that we develop. Of course, with such a wide and diverse community, it’s not easy to please everyone all of the time, but that won’t stop us trying – keep your thoughts and feedback coming to PRifeedback@kinneirdufort.com!

If you’d like to know more about KD, or the projects we work on, check out our blog posts and podcasts at www.kinneirdufort.com.

The post Designing distinctive Raspberry Pi products appeared first on Raspberry Pi.

Source: Raspberry Pi – Designing distinctive Raspberry Pi products