One topic explored in Code the Classics from Raspberry Pi Press is the origin story and success of Pong, one of the most prominent games in early video game history.

‘The success of Pong led to the creation of Pong home consoles (and numerous unofficial clones) that could be connected to a television. Versions have also appeared on many home computers.’

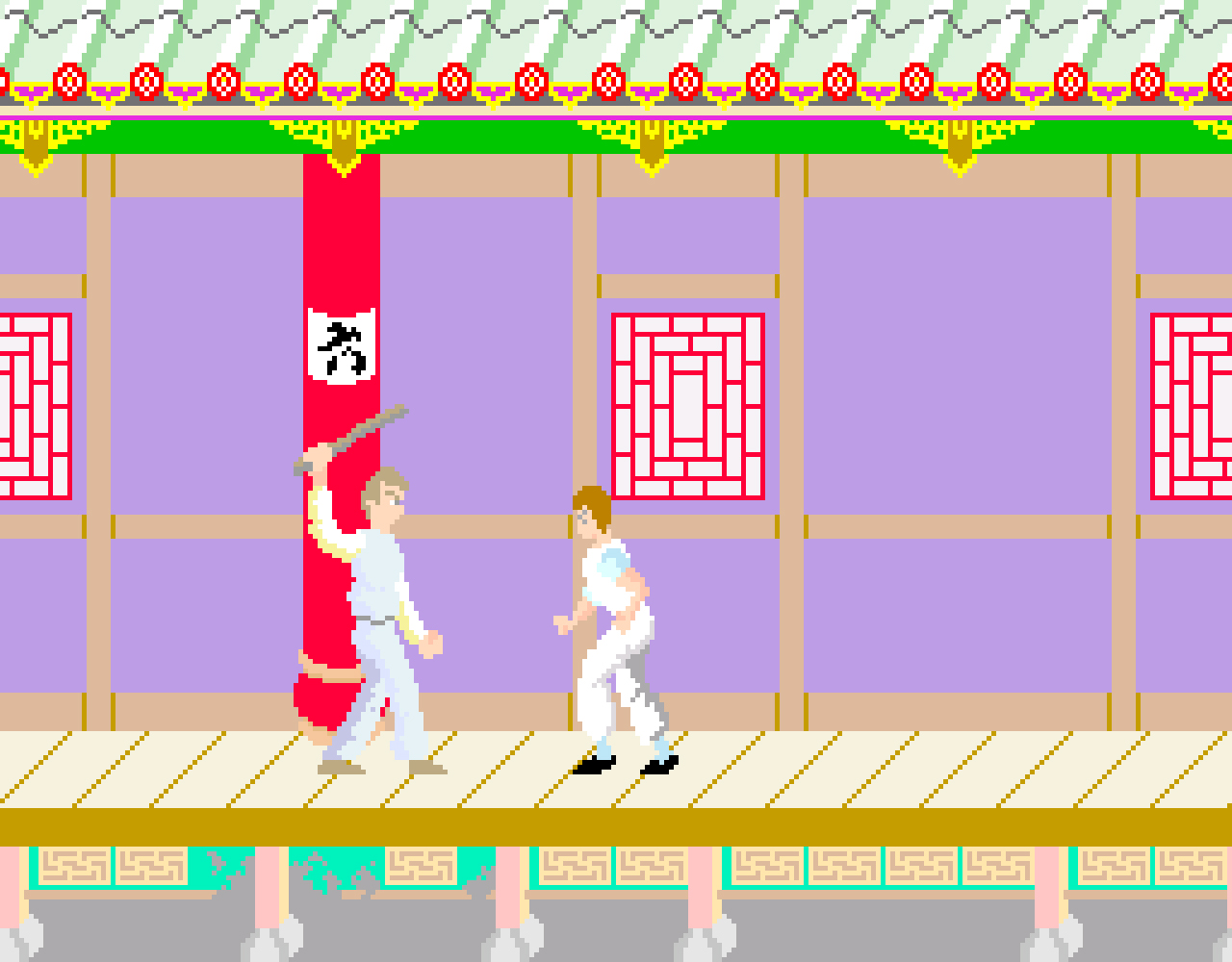

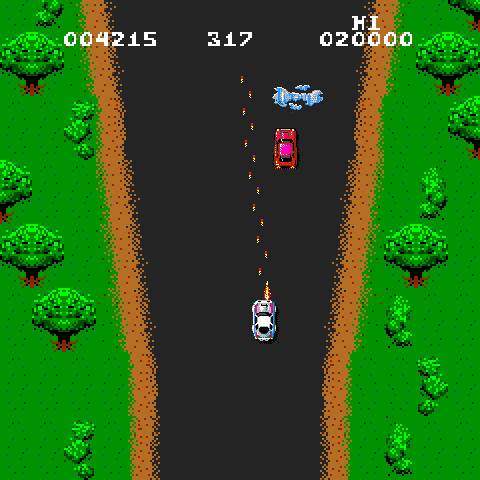

Ask anyone to describe a game of table tennis and they’ll invariably tell you the same thing: the sport involves a table split into quarters, a net dividing the two halves, a couple of paddles, and a nice round ping-pong ball to bat back and forth between two players. Take a look at the 1972 video game Pong, however, and you’ll notice some differences. The table, for instance, is simply split in half and it’s viewed side-on, the paddles look like simple lines, and the ball is square. Yet no one – not even now – would have much trouble equating the two.

Back in the early 1970s, this was literally as good as it got. The smattering of low-powered arcade machines of the time were incapable of realistic-looking graphics, so developers had to be creative, hoping imaginative gamers would fill the gaps and buy into whatever they were trying to achieve. It helped enormously that there was a huge appetite for the new, emerging video game industry at that time. Nolan Bushnell was certainly hungry for more – and had he turned his nose up at Spacewar!, a space combat game created by Steve Russell in 1962, then Pong would never even have come about.

“The most important game I played was Spacewar! on a PDP-1 when I was in college,” he says, of the two-player space shooter that was popular among computer scientists and required a $120,000 machine to run. Although the visuals were nothing to write home about, the game was one of the first graphical video games ever made. It pitted two spaceships against each other and its popularity spread, in part, because the makers decided the code could be distributed freely to anyone who wanted it. “It was a great game, fun, challenging, but only playable on a very expensive computer late at night and the wee hours of the morning,” Nolan says. “In my opinion, it was a very important step.”

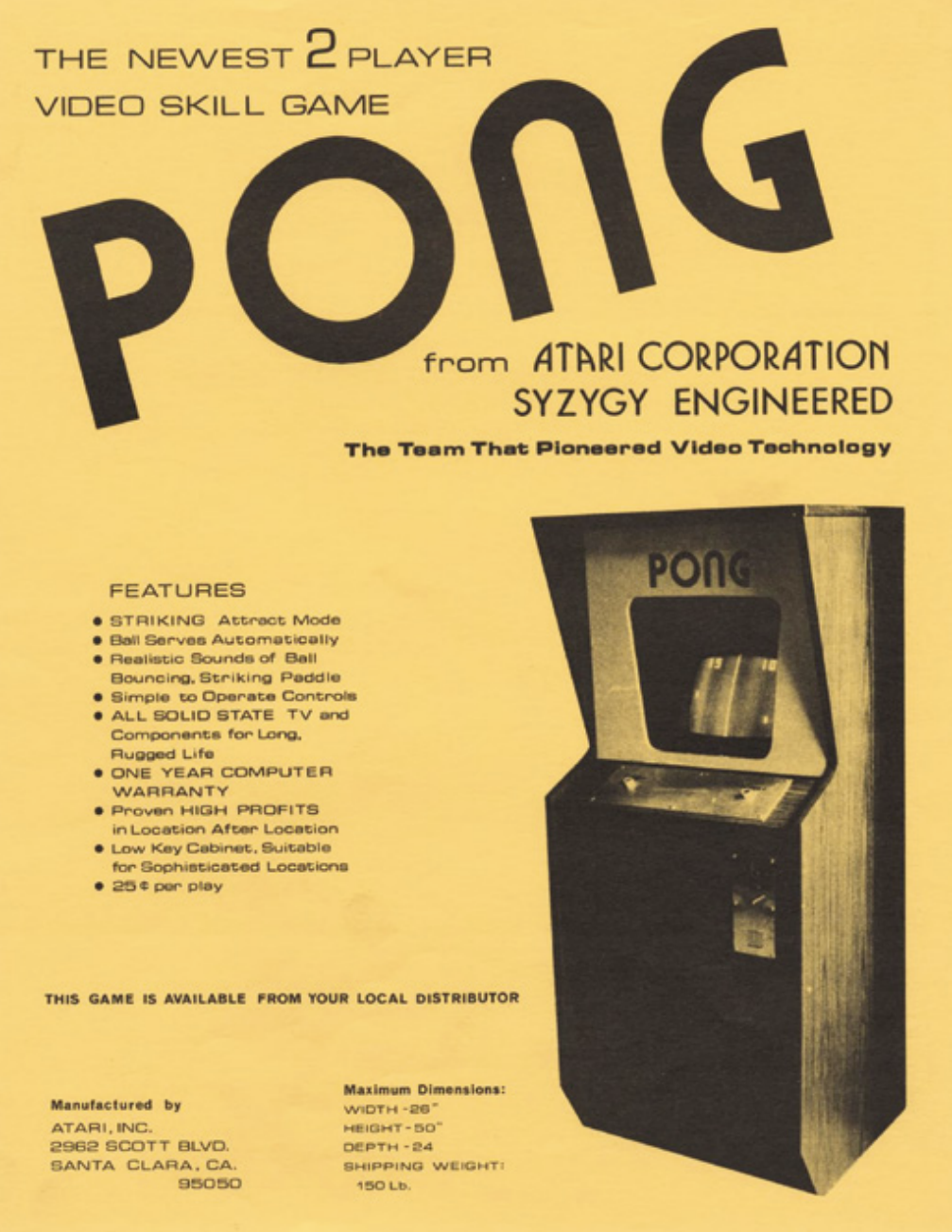

Nolan was so taken by Spacewar! that he made a version of the game with a colleague, Ted Dabney. Released in 1971, Computer Space allowed gamers to control a rocket in a battle against flying saucers, with the aim being to get more hits than the enemy in a set period of time. To make it attractive to players, it was placed in a series of colourful, space-age, moulded arcade cabinets. Nolan and Ted sold 1500 of them; even though they made just $500 from the venture, it was enough to spur them into continuing. They came up with the idea for Pong and created a company called Atari.

One of their best moves was employing engineer Al Alcorn, who had worked with Nolan at the American electronics company Ampex. Al was asked to create a table tennis game based on a similar title that had been released on the Magnavox Odyssey console, on the pretence that the game would be released by General Electric. In truth, Nolan simply wanted to work out Al’s potential, but he was blown away by what his employee came up with. Addictive and instantly recognisable, Atari realised Pong could be a major hit. The game’s familiarity with players meant it could be picked up and played by just about anyone.

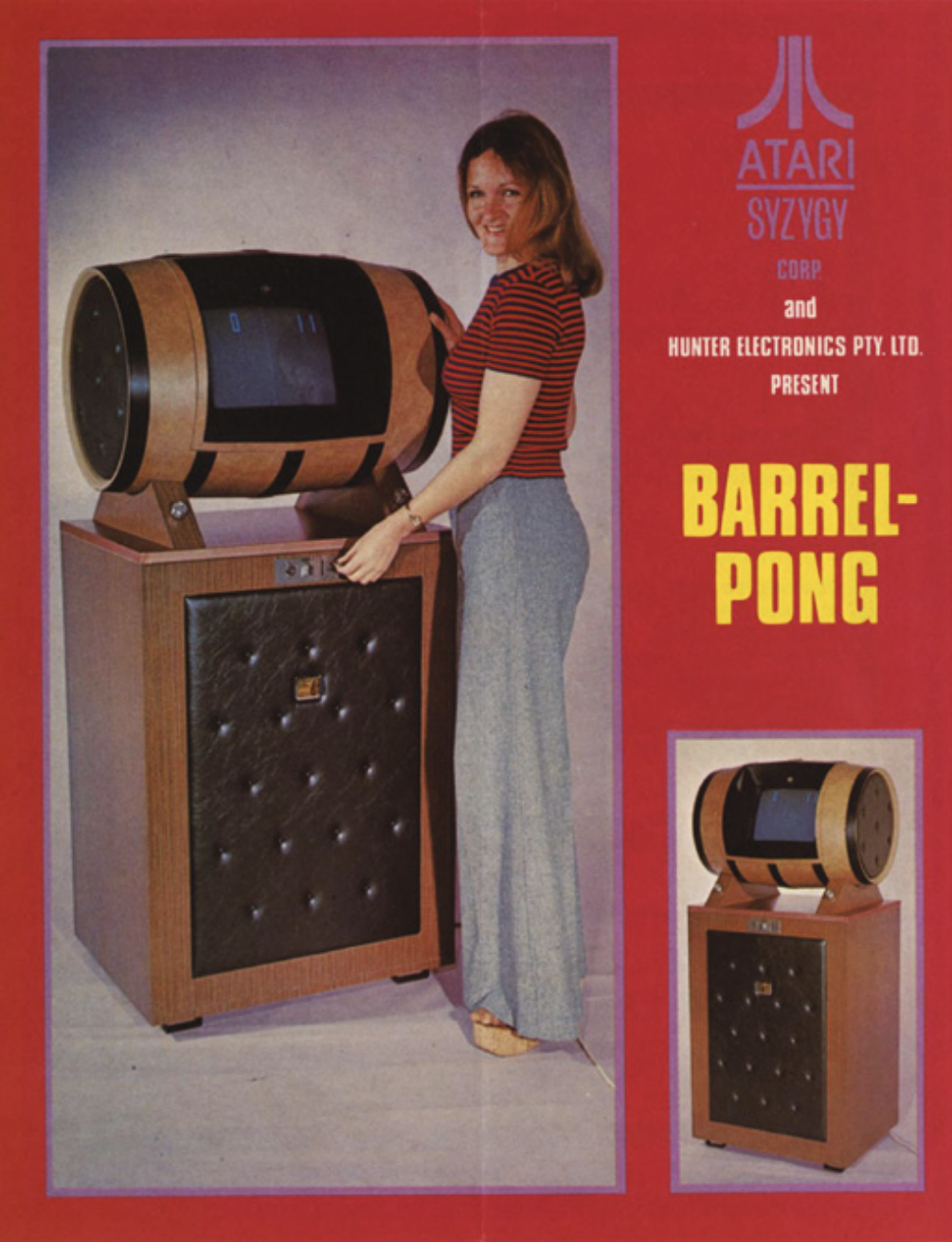

Even so, Nolan had a hard time convincing others. Manufacturers turned the company down, so he visited the manager of a bar called Andy Capp’s in Sunnyvale, California and asked them to take Pong for a week. The manager soon had to call Nolan to tell him the machine had broken: it had become stuffed full of quarters from gamers who loved the game. By 1973, production of the cabinet was in overdrive and 8000 were sold. It led to the creation of a Pong home console which sold more than 150,000 machines. People queued to get their hands on one and Atari was on its way to become a legendary games company.

For Nolan, it was justification for his perseverance and belief. Suddenly, the man who had become interested in electronics at school, where he would spend time creating devices and connecting bulbs and batteries, was being talked of as a key player in the fledgling video game industry. But what did Nolan, Ted, Al, and the rest of the Atari team do to make the game so special? “We made it a good, solid, fun game to play,” says Nolan. “And we made it simple, easy, and quickly understood. Keeping things simple is more difficult to do than building something complex. You can’t dress up bad gameplay with good graphics.”

Making Pong

On the face of it, Pong didn’t look like much. Each side had a paddle that could be moved directly up and down using the controller, and the ball would be hit from one side to the other. The score was kept at the top of the screen and the idea was to force the opposing player to miss. It meant the game program needed to determine how the ball was hit and where the ball would go from that point. And that’s the crux of Pong’s success: the game encouraged people to keep playing and learning in the hope of attaining the skills to become a master.

When creating Pong, then, the designers had a few things in mind. One of the most important parts of the game was the movement of the paddles. This involved a simple, vertical rectangle that went up and down. One of the benefits Atari had when it created Pong was that it controlled not just the software but the hardware too. By building the cabinet, it was able to determine how those paddles should be moved. “The most important thing if you want to get the gameplay right is to use a knob to move the paddle,” advises Nolan. “No one has done a good Pong using touchscreens or a joystick.”

Look at a Pong cabinet close up – there are plenty of YouTube videos which show the game in action on the original machine – and you will see what Nolan means. You’ll notice that players turned a knob anticlockwise to move the paddle down, and clockwise to move it up. Far from being confusing, it felt intuitive.

Movement of the ball

With the paddles moving, Atari’s developers were able to look at the movement of the ball. At its most basic, if the ball continued to make contact with the paddles, it would constantly move back and forth. If it did not make contact, then it would continue moving in the direction it had embarked upon and leave the screen. At this stage, a new ball was introduced in the centre of the screen and the advantage was given to the player who had just chalked up a point. If you watch footage of the original Pong, you will see that the new ball was aimed at the player who had just let the ball go past. There was a chance he or she would miss again.

To avoid defeat, players had to be quite nifty on the controls and stay alert. Watching the ball go back and forth at great speed could be quite mesmerising as it left a blurred trail across the cathode ray tube display. There was no need to waste computing power by animating the ball because the main attention was focused on what would happen when it collided with the paddle. It had to behave as you’d expect. “The game did not exist without collisions of the ball to the paddle,” says Nolan.

Al realised that the ball needed to behave differently depending on where it hit the paddle. When playing a real game of tennis, if the ball hits the centre of the racket, it will behave differently from a ball that hits the edge. Certainly, the ball is not going to be travelling in a simple, straight path back and forth as you hit it; it is always likely to go off at an angle. This, though, is the trickiest part of making Pong “The ball should bounce up from an upper collision with more obtuse angles as the edge of the paddle is approached,” Nolan says. “This balances the risk of missing with the fact that an obtuse angle is harder to return.” This is what Pong is all about: making sure you hit the ball with the paddle, but in a manner that makes it difficult for the opposing player to return it. “A player wants the ball to be just out of reach for the opponent or be hard for him or her to predict.”

Read on…

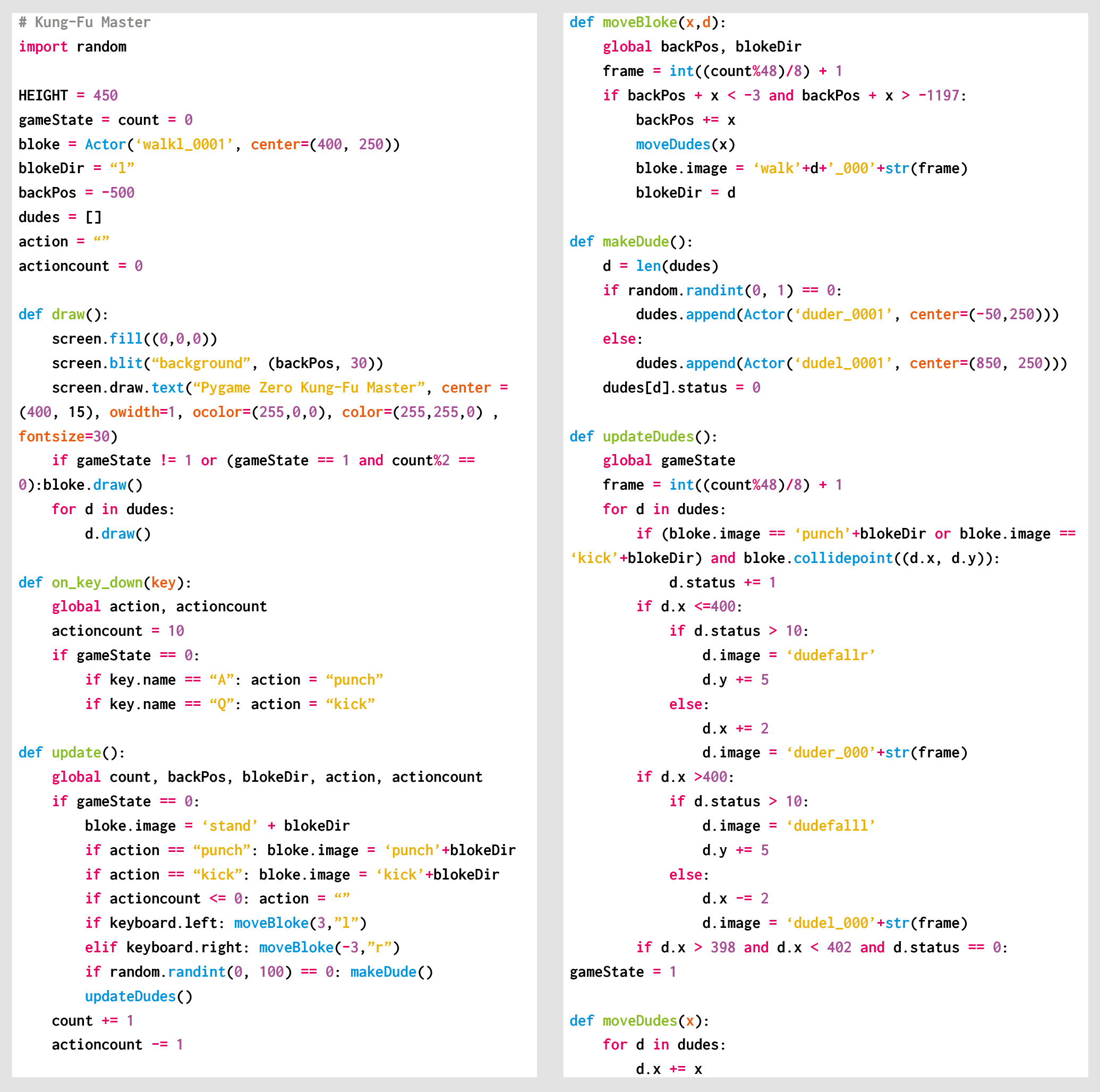

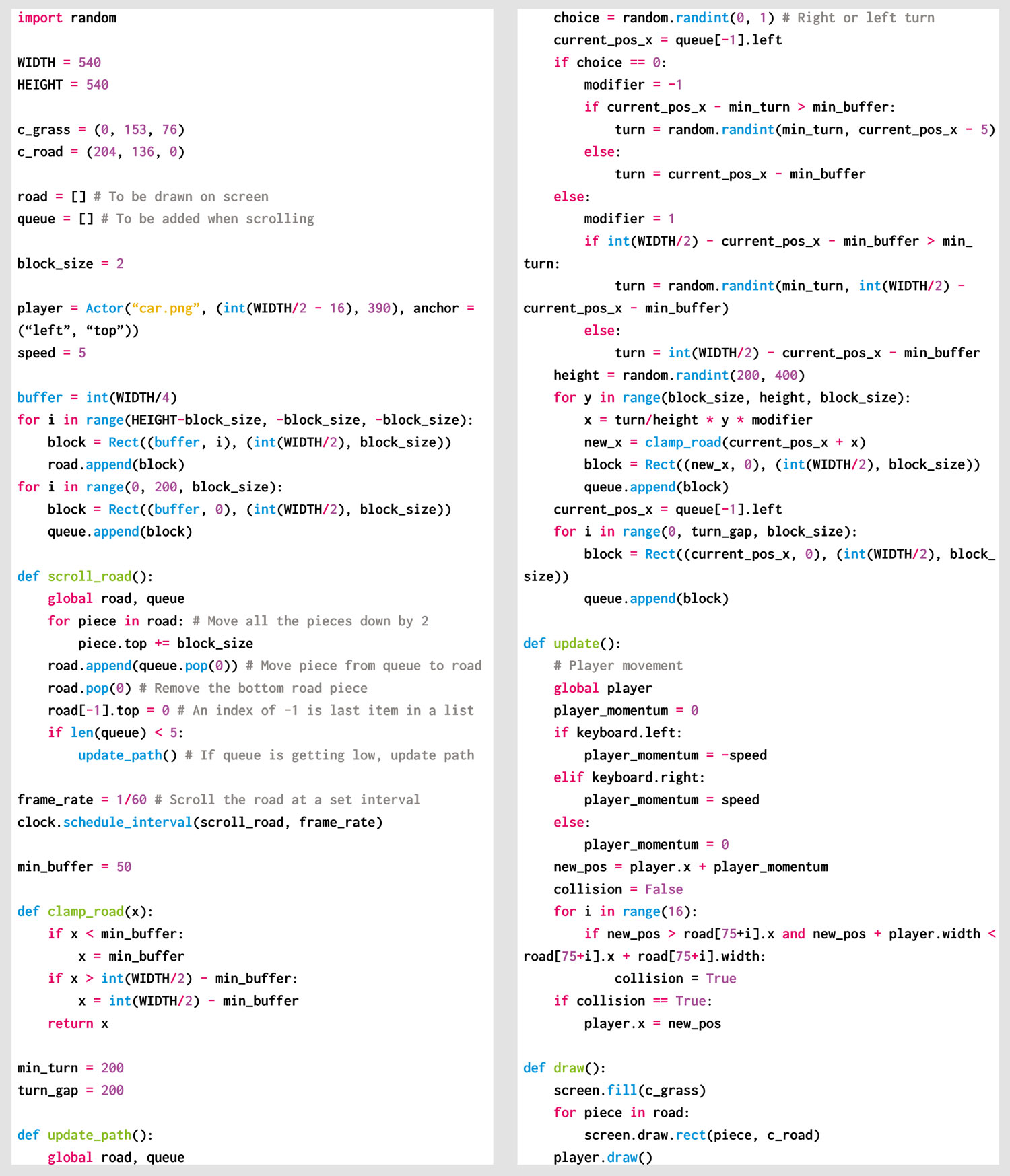

This post is part of a much longer deep dive into the history of Pong in Code the Classics, our 224-page hardback book that not only tells the stories of some of the seminal video games of the 1970s and 1980s, but also shows you how to use Python and Pygame Zero to create your own games inspired by them, following examples programmed by Raspberry Pi founder Eben Upton.

In conjunction with today’s blog post, we’re offering £1 off Code the Classics when you order your copy between now and midnight Wednesday 26 Feb 2020 from the Raspberry Pi Press online store. Simply follow this link or enter the discount code PONG at checkout to get your copy for only £11, with free shipping in the UK.

Code the Classics is also available as a free download, although the physical book is rather delightful, so we really do recommend purchasing it.

The post The History of Pong | Code the Classics appeared first on Raspberry Pi.

Source: Raspberry Pi – The History of Pong | Code the Classics