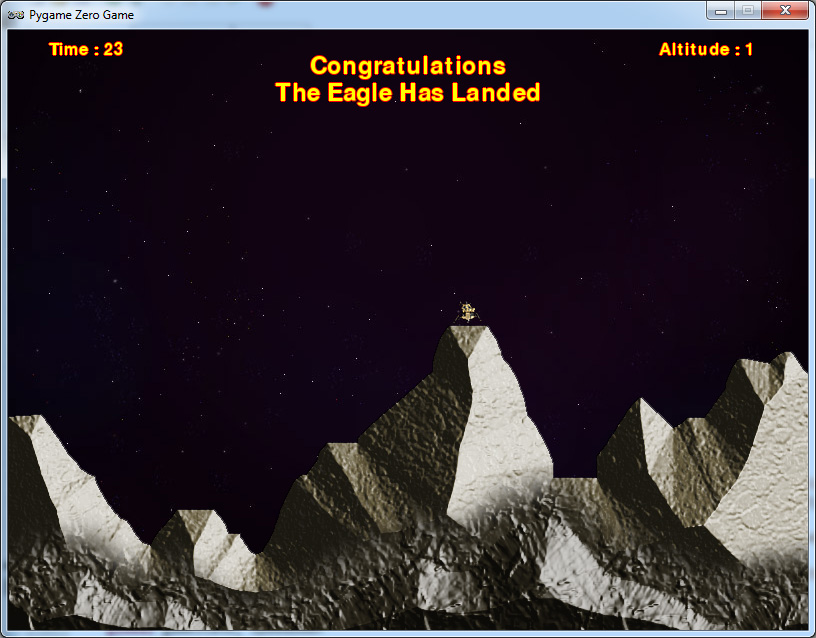

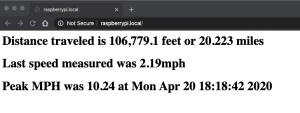

Do you want to make a sensor with a battery life you can measure in days rather than hours? Even if it contains a (relatively!) power-hungry device like a Raspberry Pi? By cunning use of a real-time clock module, you can make something that wakes up, does its thing, and then goes back to sleep. While asleep, the sensor will sip a tiny amount of current, making it possible to remotely monitor the temperature of your prize marrow in the greenhouse for days on end from a single battery. Read on to find out how to do it.

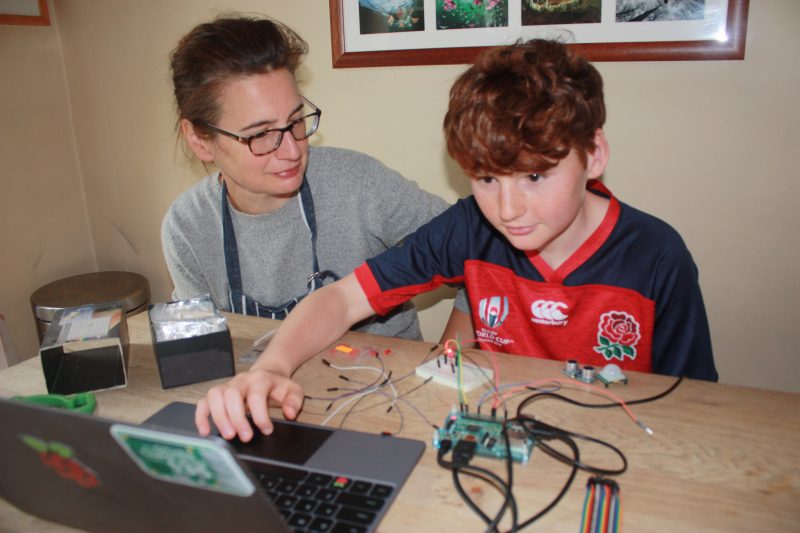

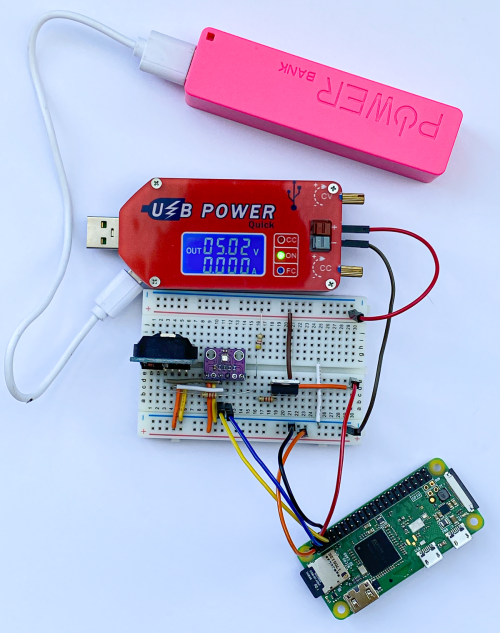

A sleeping Raspberry Pi Zero apparently consuming no current!

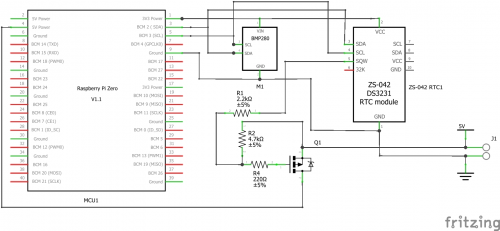

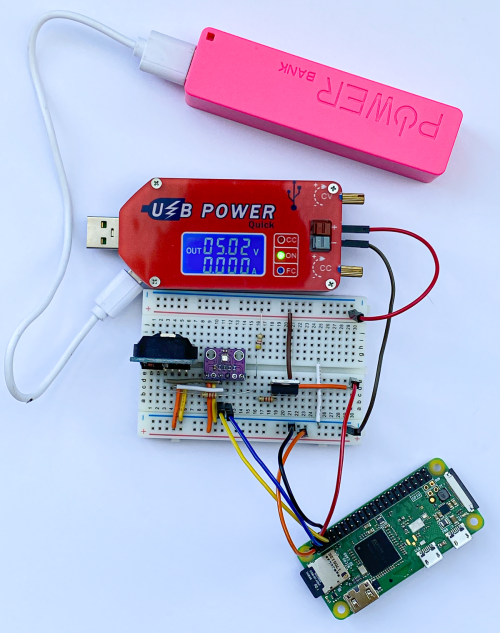

You’ll need:

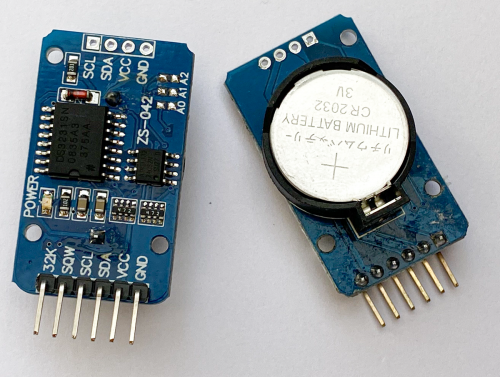

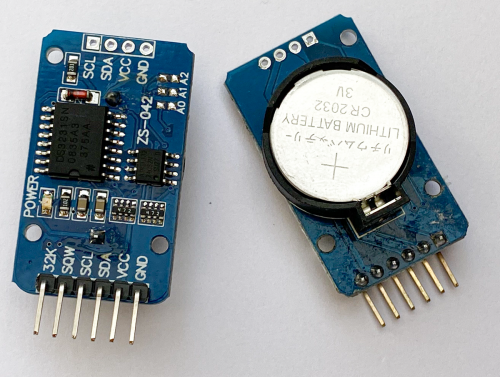

- DS3231 powered real-time clock module with battery backup: make sure it has a battery holder and an INT/SQW output pin

- P-channel MOSFET: the IRF9540N works well

- Three resistors: 2.2 kΩ, 4.7 kΩ, and 220 Ω

- A device you want to control: this can be a PIC, Arduino, ESP8266, ESP32, or Raspberry Pi. My software is written in Python and works in MicroPython or on Raspberry Pi, but you can find DS3231 driver software for lots of devices

- Sensor you want to use: we’re using a BME280 to get air temperature, pressure, and humidity

- Breadboard or prototype board to build up the circuit

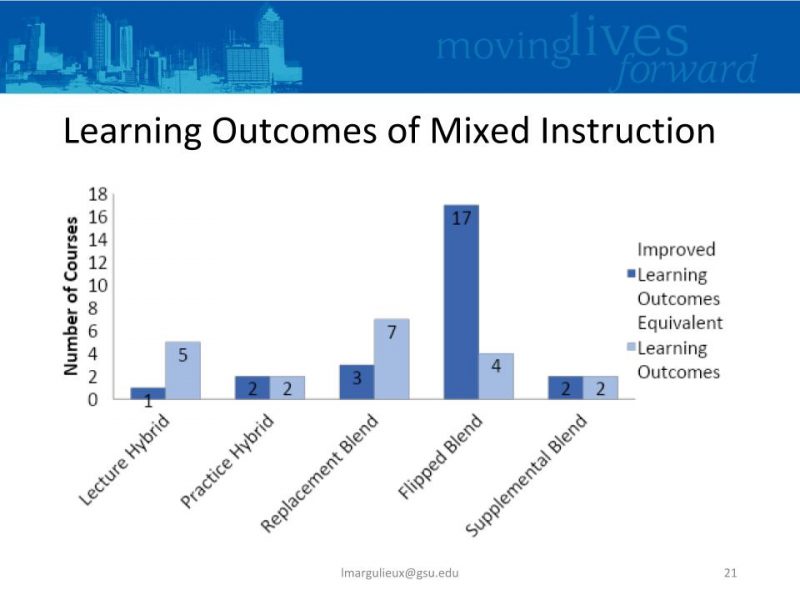

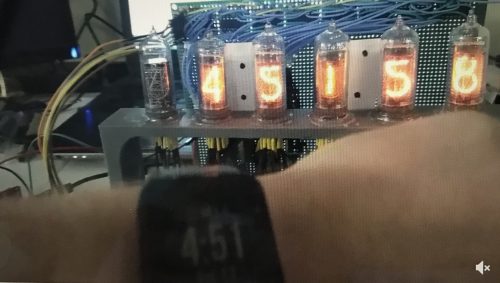

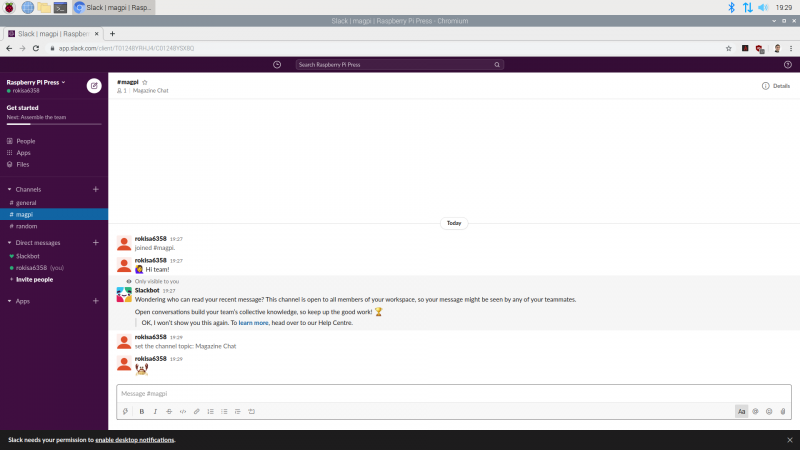

We’ll be using a DS3231 real-time clock which is sold in a module, complete with a battery. The DS3231 contains two alarms and can produce a trigger signal to control a power switch. To keep our software simple, we are going to implement an interval timer, but there is nothing to stop you developing software that turns on your hardware on particular days of the week or days in the month. The DS3231 is controlled using I2C, which means it can be used with lots of devices.

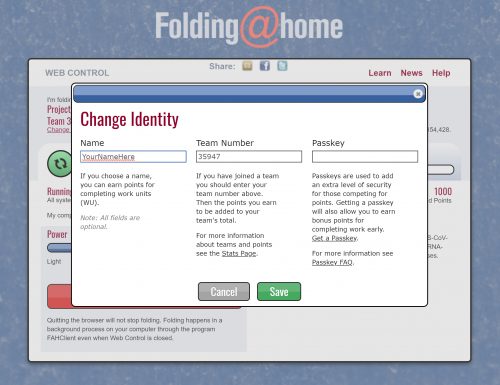

You can pick up one of these modules from lots of suppliers. Make sure that you get one with the SQW connection, as that provides the alarm signal

MOSFET accompli

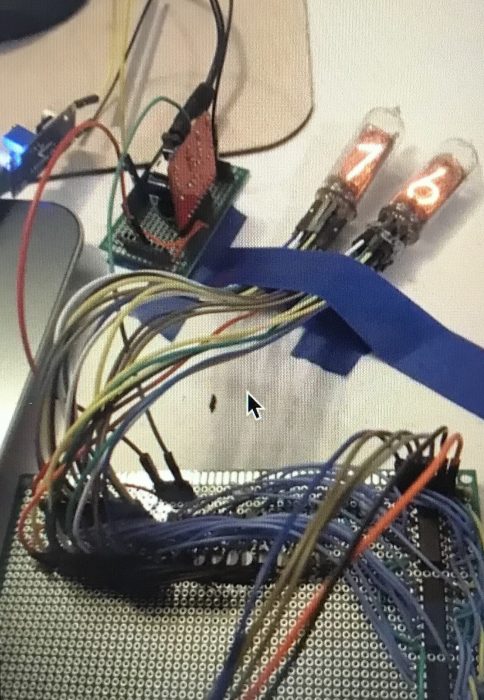

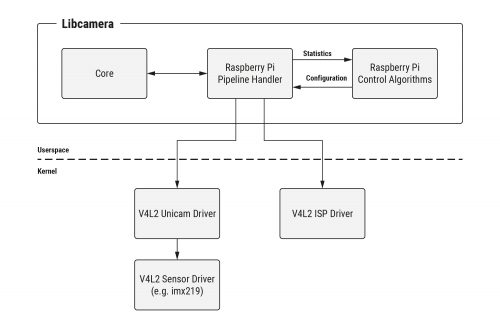

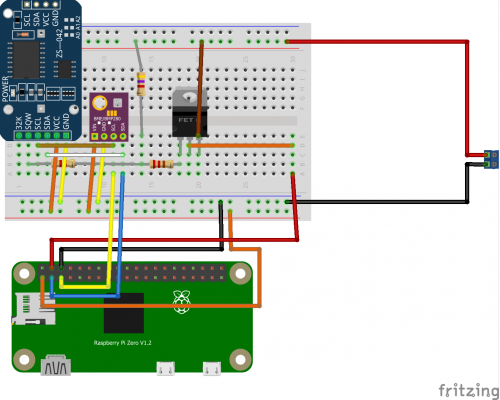

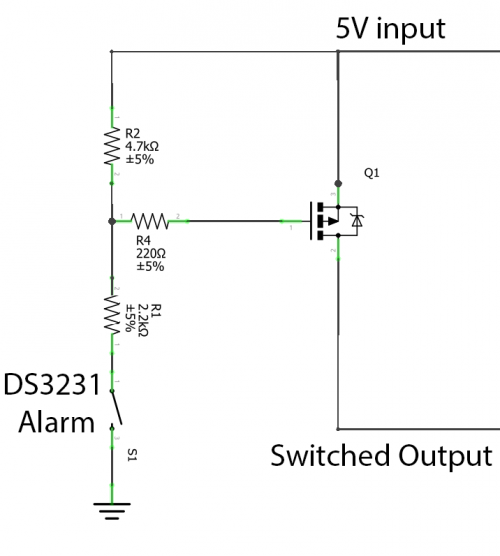

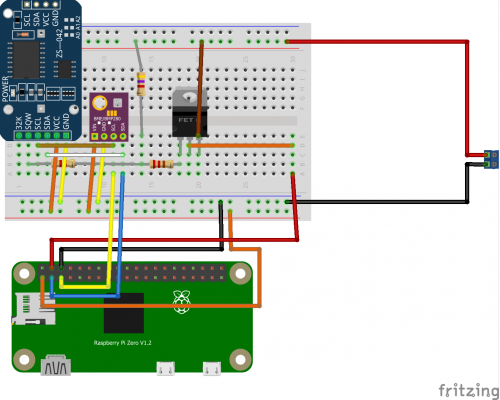

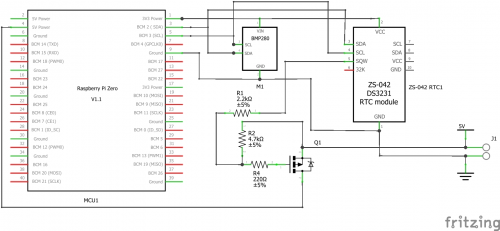

The power to our Raspberry Pi Zero is controlled via a P-channel MOSFET device operating as a switch. The 3.3 V output from Raspberry Pi is used to power the DS3231 and our BME280 sensor. The gate on the MOSFET is connected via a resistor network to the SQW output from the DS3231.

You can think of a MOSFET as a kind of switch. It has a source pin (where we supply power), a drain pin (which is the output the MOSFET controls), and a gate pin. If we change the voltage on the gate pin, this will control whether the MOSFET conducts or not.

We use a P-channel MOSFET to switch the power because the gate voltage must be pulled down to cause the MOSFET to conduct, and that is how P-channel devices function.

MOSFET devices are all about voltage. Specifically, when the voltage difference between the source and the gate pin reaches a particular value, called the threshold voltage, the MOSFET will turn on. The threshold voltage is expressed as a negative value because the voltage on the gate must be lower than the voltage on the source. The MOSFET that we’re using turns on at a threshold voltage of around -3.7 volts and off at a voltage of -1.75 volts.

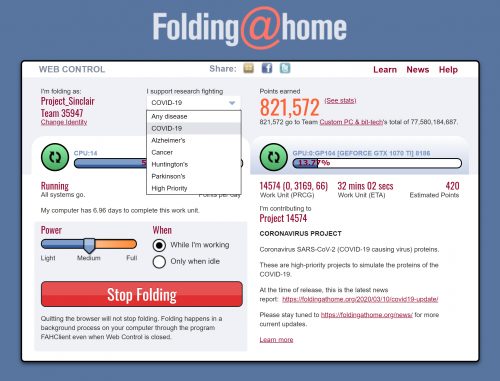

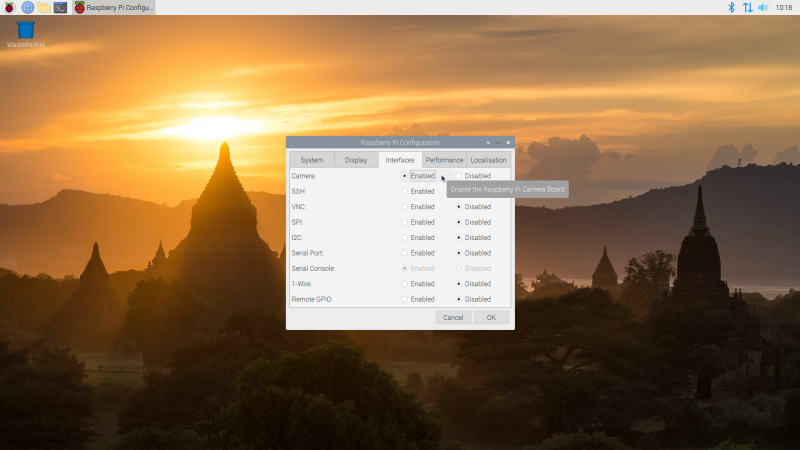

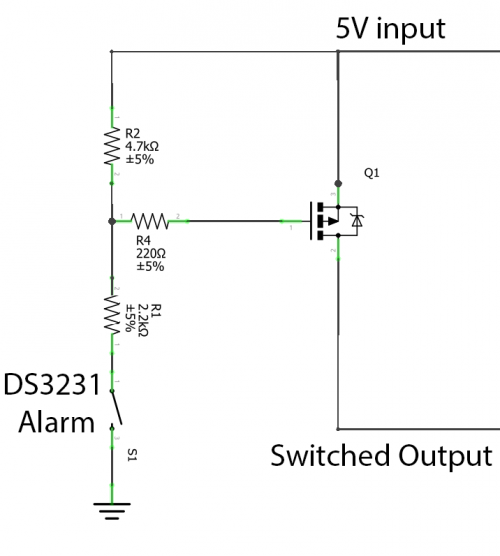

The SQW signal from the DS3231 is controlled by a transistor which is acting as a switch connected to ground inside the DS3231. When the alarm is triggered, this transistor is turned on, connecting the SQW pin to ground. The diagram below shows how this works.

The resistors R1 and R2 are linked to the supply voltage at one end and the SQW pin and the MOSFET gate on the other. When SQW is turned off the voltage on the MOSFET gate is pulled high by the resistors, so the MOSFET turns off. When SQW is turned on, it pulls the voltage on the MOSFET gate down, turning it on.

Unfortunately, current leaking through R1 and R2 to the DN3231 means that we are not going to get zero current consumption when the MOSFET is turned off, but it is much less than 1 milliamp.

We’re using a BME280 environmental sensor on this device. It is connected via I2C to Raspberry Pi. You don’t need this sensor to implement the power saving

Power control

Now that we have our hardware built, we can get some code running to control the power. The DS3231 is connected to Raspberry Pi using I2C. Before you start, you must enable I2C on your Raspberry Pi using the raspi-config tool. Use sudo raspi-config and select Interfacing Options. Next, you need to make sure that you have all the I2C libraries installed by issuing this command at a Raspberry Pi console:

sudo apt-get install python3-smbus python3-dev i2c-tools

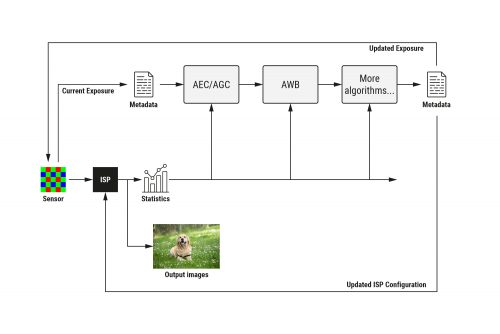

The sequence of operation of our sensor is as follows:

- The program does whatever it needs to do. This is the action that you want to perform at regular intervals. That may be to read a sensor and send the data onto the network, or write it to a local SD card or USB memory key. It could be to read something and update an e-ink display. You can use your imagination here.

- The program then sets an alarm in the DS3231 at a point in the future, when it wants the power to come back on.

- Finally, the program acknowledges the alarm in the DS3231, causing the SQW alarm output to change state and turn off the power.

Clock setting

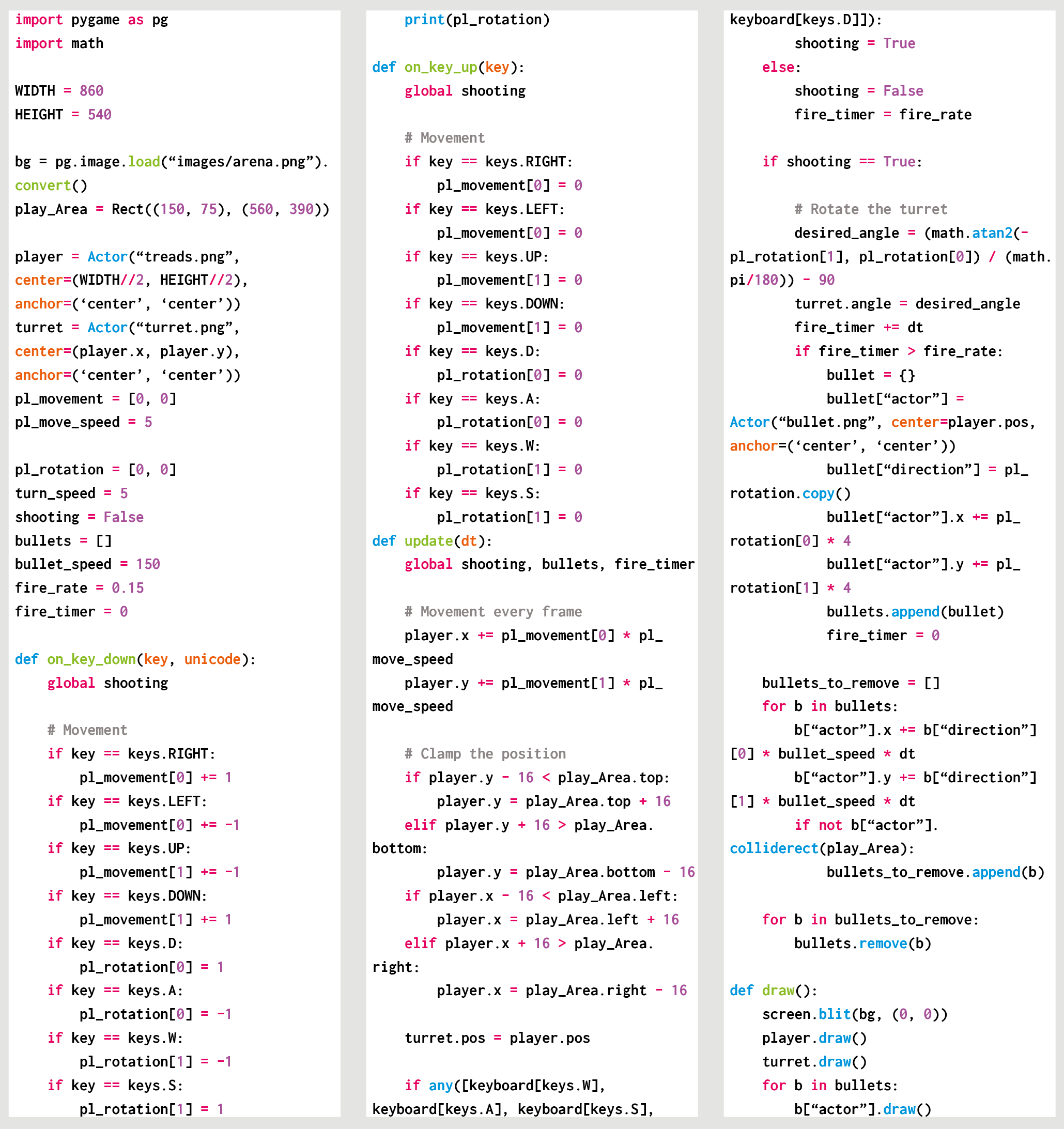

The program below only uses a fraction of the capabilities of the DS3231 device. It creates an interval timer that can time hours, minutes, and seconds. Each time the program runs, the clock is set to zero, and the alarm is configured to trigger when the target time is reached.

Put the program into a file called SensorAction.py on your Raspberry Pi, and put the code that you want to run into the section indicated.

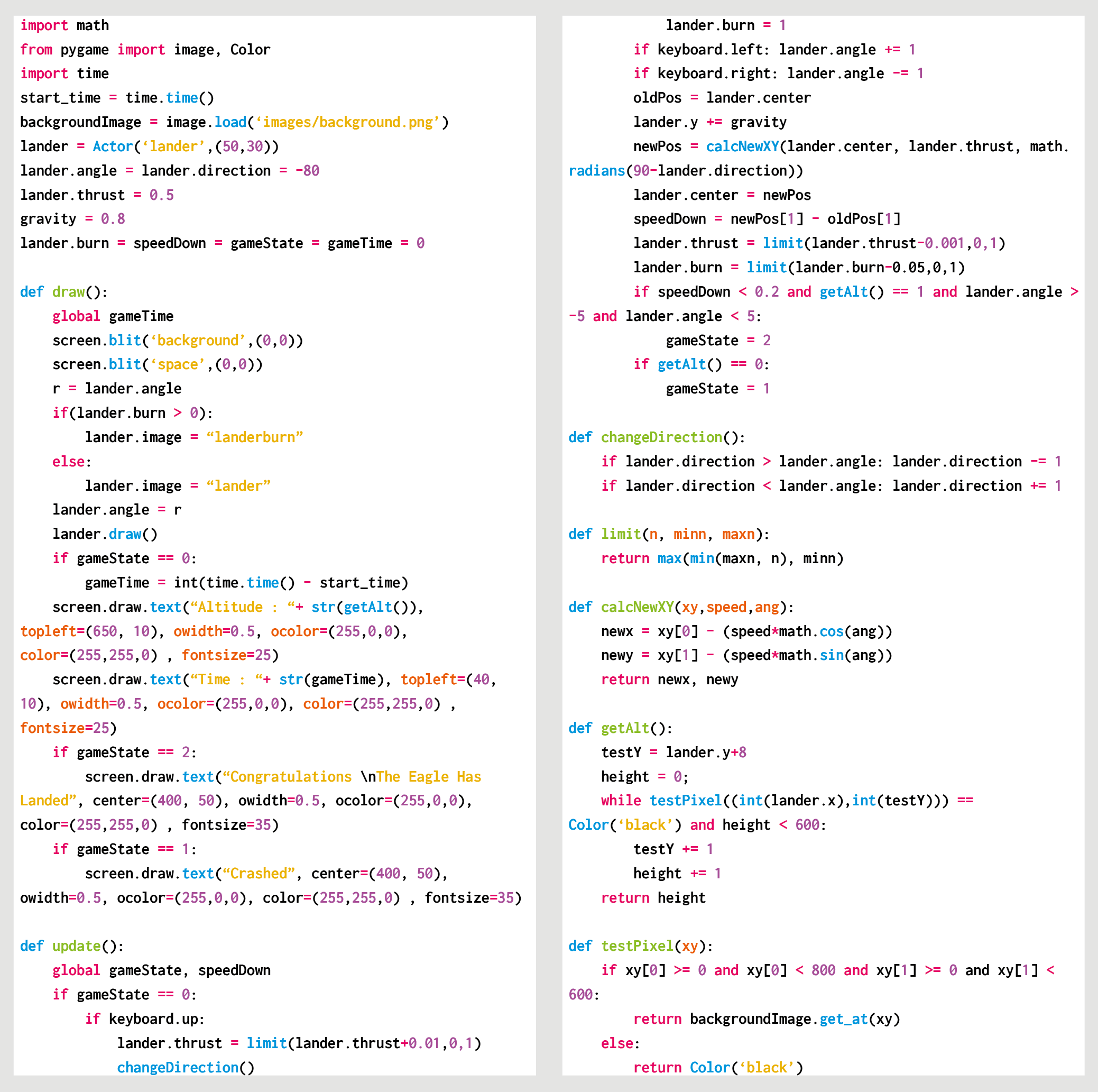

import smbus

bus = smbus.SMBus(1)

DS3231 = 0x68

SECONDS_REG = 0x00

ALARM1_SECONDS_REG = 0x07

CONTROL_REG = 0x0E

STATUS_REG = 0x0F

def int_to_bcd(x):

return int(str(x)[-2:], 0x10)

def write_time_to_clock(pos, hours, minutes, seconds):

bus.write_byte_data(DS3231, pos, int_to_bcd(seconds))

bus.write_byte_data(DS3231, pos + 1, int_to_bcd(minutes))

bus.write_byte_data(DS3231, pos +2, int_to_bcd(hours))

def set_alarm1_mask_bits(bits):

pos = ALARM1_SECONDS_REG

for bit in reversed(bits):

reg = bus.read_byte_data(DS3231, pos)

if bit:

reg = reg | 0x80

else:

reg = reg & 0x7F

bus.write_byte_data(DS3231, pos, reg)

pos = pos + 1

def enable_alarm1():

reg = bus.read_byte_data(DS3231, CONTROL_REG)

bus.write_byte_data(DS3231, CONTROL_REG, reg | 0x05)

def clear_alarm1_flag():

reg = bus.read_byte_data(DS3231, STATUS_REG)

bus.write_byte_data(DS3231, STATUS_REG, reg & 0xFE)

def check_alarm1_triggered():

return bus.read_byte_data(DS3231, STATUS_REG) & 0x01 != 0

def set_timer(hours, minutes, seconds):

# zero the clock

write_time_to_clock(SECONDS_REG, 0, 0, 0)

# set the alarm

write_time_to_clock(ALARM1_SECONDS_REG, hours, minutes, seconds)

# set the alarm to match hours minutes and seconds

# need to set some flags

set_alarm1_mask_bits((True, False, False, False))

enable_alarm1()

clear_alarm1_flag()

#

# Your sensor behaviour goes here

#

set_timer(1,30,0)

The set_timer function is called to set the timer and clear the alarm flag. This resets the alarm signal and powers off the sensor. The example above will cause the sensor to shut down for 1 hour 30 minutes.

You can use any other microcontroller that implements I2C

Power down

The SensorAction program turns off your Raspberry Pi without shutting it down properly, which is something your mother probably told you never to do. The good news is that in extensive testing, we’ve not experienced any problems with this. However, if you want to make your Raspberry Pi totally safe in this situation, you should make its file system ‘read-only’, which means that it never changes during operation and therefore can’t be damaged by untimely power cuts. There are some good instructions from Adafruit here: hsmag.cc/UPgJSZ.

Note: making the operating system file store read-only does not prevent you creating a data logging application, but you would have to log the data to an external USB key or SD card and then dismount the storage device before killing the power.

If you are using a different device, such as an ESP8266 or an Arduino, you don’t need to worry about this as the software in them is inherently read-only.

The SQW output from the DS3231 will pull the gate of the MOSFET low to turn on the power to Raspberry Pi

Always running

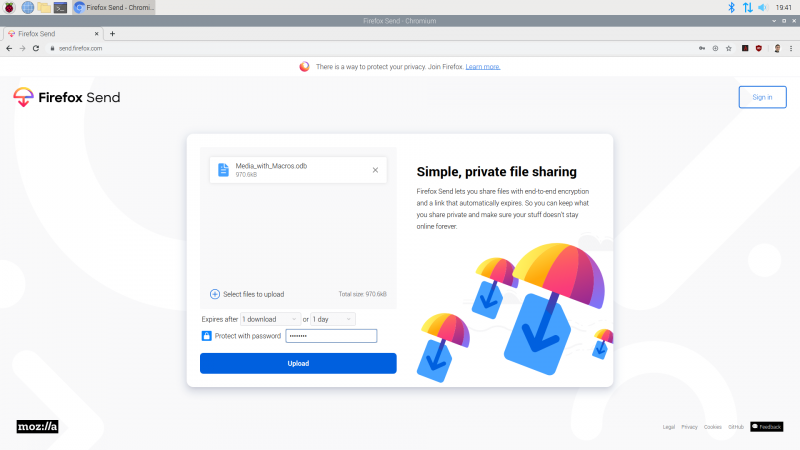

To get the program to run when the Raspberry Pi boots, use the Nano editor to add a line at the end of the rc.local file that runs your program.

sudo nano /etc/rc.local

Use the line above at the command prompt to start editing the rc.local file and add the following line at the end of the file:

python3 /home/pi/SensorAction.py &

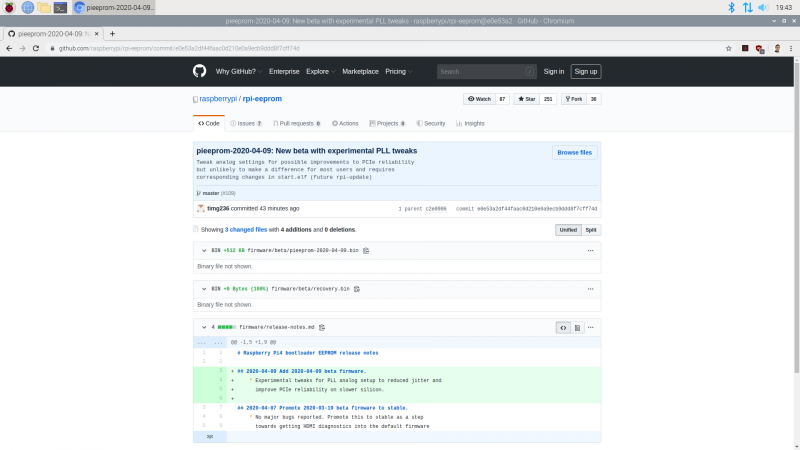

This statement runs Python 3, opens the SensorAction.py file, and runs it. Don’t forget the ampersand (&) at the end of the command: this starts your program as a separate process, allowing the boot to complete. Now, when Raspberry Pi boots up, it will run your program and then shut itself down. You can find a full sample application on the GitHub pages for this project (hsmag.cc/Yx7q6t). It logs air temperature, pressure, and humidity to an MQTT endpoint at regular intervals. Now, go and start tracking that marrow temperature!

Issue 30 of HackSpace magazine is out now

The latest issue of HackSpace magazine is on sale now, and you can get your copy from the Raspberry Pi Press online store. You can also download it for free to check it out first.

UK readers can take advantage of our special subscriptions offer at the moment.

3 issues for £10 & get a free book worth £10…

If you’re in the UK, get your first three issues of HackSpace magazine, The MagPi, Custom PC, or Digital SLR Photography delivered to your door for £10, and choose a free book (itself worth £10) on top!

The post Build low-power, clock-controlled devices appeared first on Raspberry Pi.

Source: Raspberry Pi – Build low-power, clock-controlled devices