In issue 32 of HackSpace magazine, out now, we talk to Gina Häußge, creator of OctoPrint – it sits on a Raspberry pi and monitors your 3D printer.

Gina Häußge, creator and maintainer of OctoPrint

There’s something enchanting about watching a 3D printer lay down hot plastic. Seeing an object take shape before your eyes is utterly compelling, which is perhaps why we love watching 3D printing time-lapse videos so much.

Despite this, it would be impractical and inefficient to sit and watch every time you sent a print job through. That’s why we should all be grateful for OctoPrint. This free, open-source software monitors your 3D printer for you, keeping you from wasting plastic and ensuring that you can go about your business without fearing for your latest build.

OctoPrint is the creation of Gina Haüßge. We enjoyed a socially distant chat with her about the challenges of running an open-source project, making, and what it’s like to have a small project become huge.

HackSpace: Most people who have used a 3D printer will have heard of OctoPrint, but for the benefit of those who haven’t, what is it?

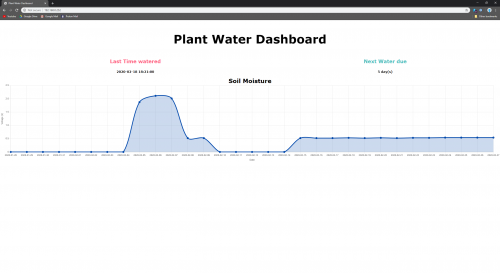

Gina Haüßge: Somebody once called it a baby monitor for your 3D printer. I really like this description. It’s pretty much a combination of a baby monitor and a remote control, because it allows you to go through any web browser on your network and monitor what your printer is currently up to, how much the current job has progressed. If you have a webcam set up, it can show you the print itself, so you can see that everything is working correctly, it’s still on the bed, and all that.

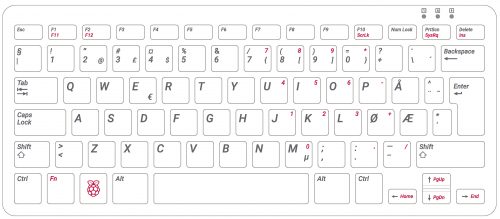

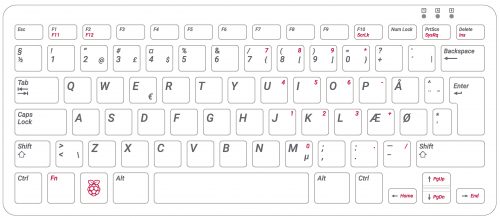

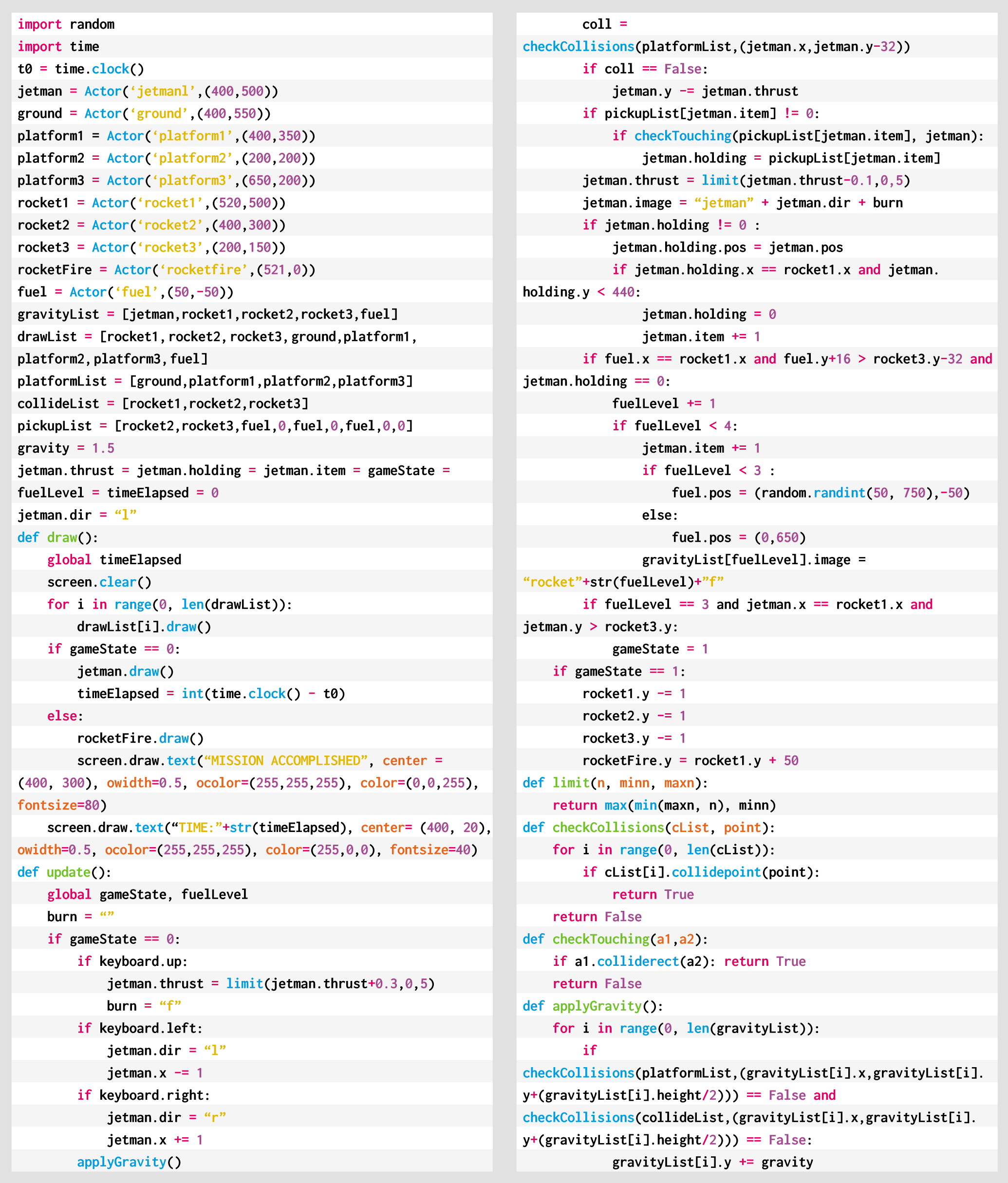

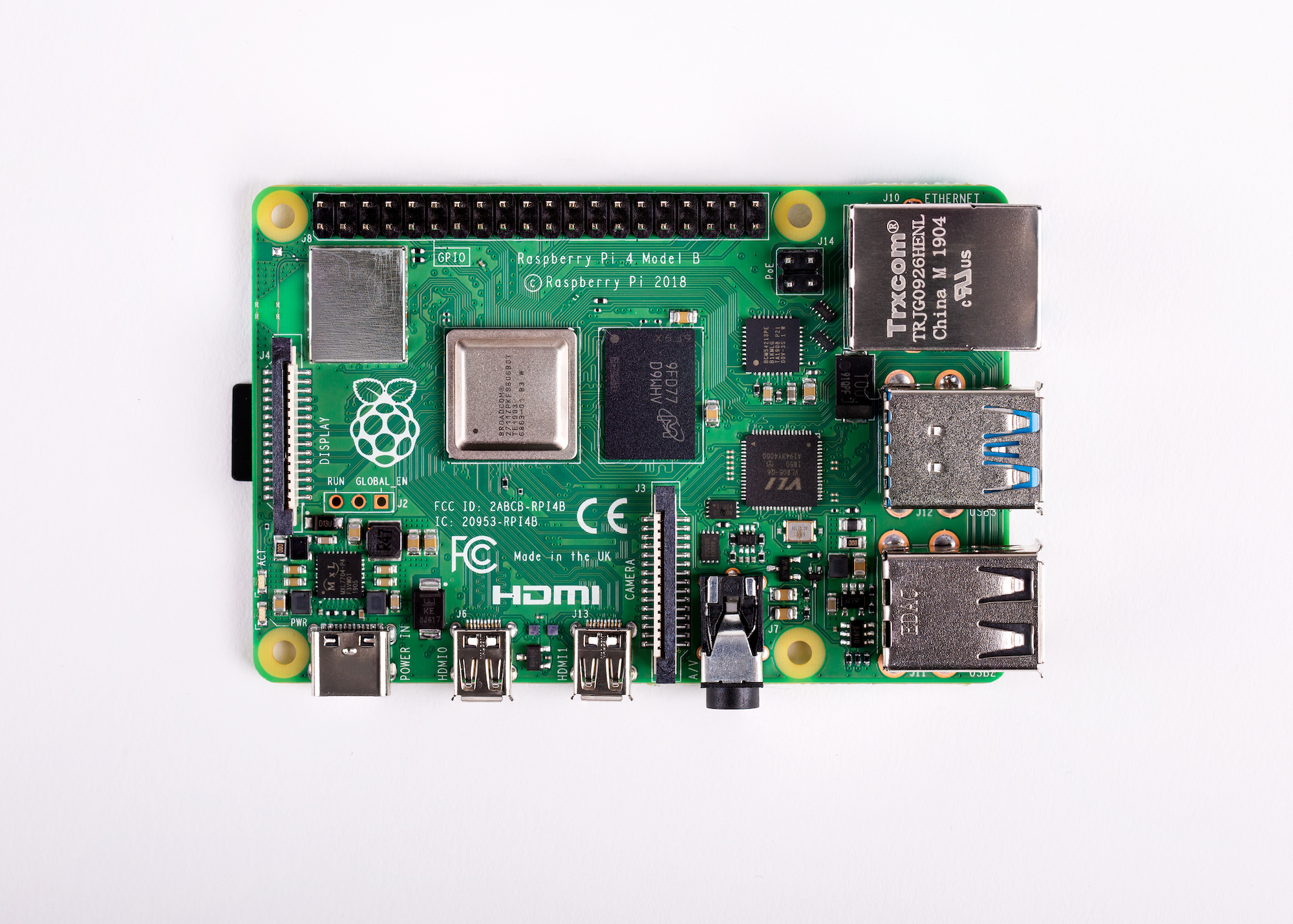

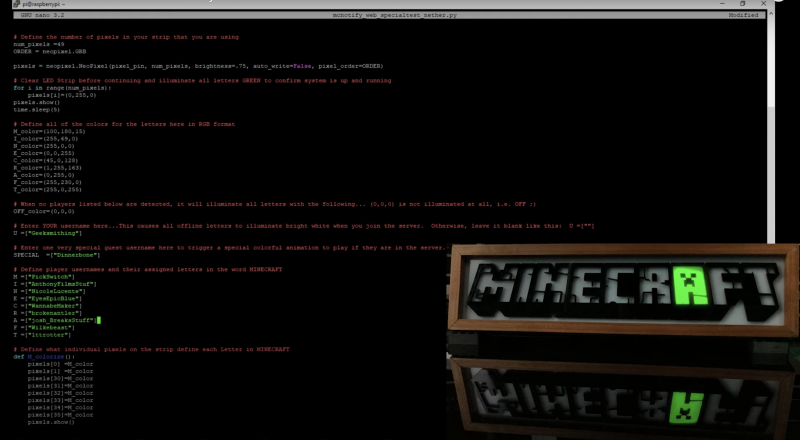

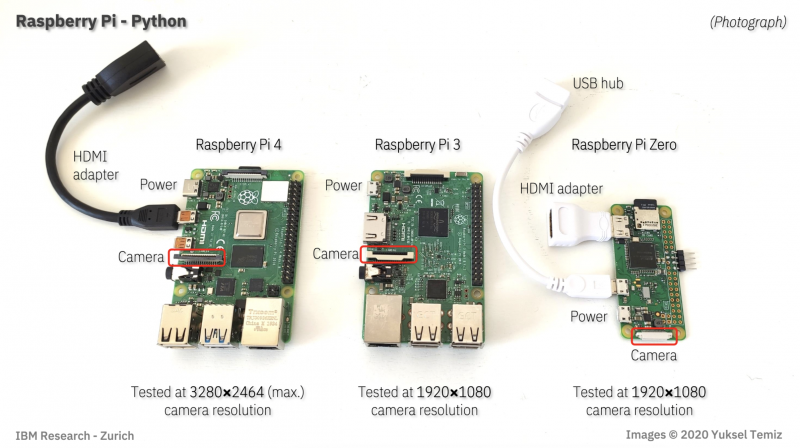

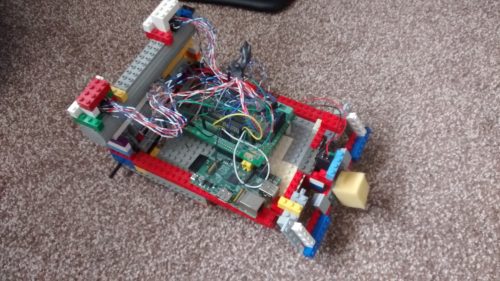

It also offers a plug-in interface so that it can be expanded with various features and functionality, and people have written a ton of integrations with notification systems. And all of this runs on pretty much any system that runs Python. I have to say Python, not MicroPython, the full version. Usually Linux, and the most common use case is to run it on a Raspberry Pi, and this is also how I originally set it out to work.

Most people think it only runs on a Raspberry Pi, but no. It will run on any old laptop that you still have lying around. It’s cross-platform, so you don’t need to buy a Raspberry Pi if you have another machine that will fit the bill.

OctoPrint is most commonly run on a Raspberry Pi

HS: How long have you been working on it?

GH: I originally sat down to write it over my Christmas break in 2012, because I had got my first 3D printer back then. It was sitting in my office producing fumes and noise for hours on end, which was annoying when trying to work, or game, or anything else.

I thought there must be a solution involving attaching one of these nifty new Raspberry Pis that had just come out. Someone must have written something, right? I browsed around the internet, realised that the closest thing to what I was looking for treated the printer as a black box – to fire job data at it and hope that it gets it right. That was not what I wanted; I wanted this feedback channel. I wanted to see what was happening; I wanted to monitor the temperatures; I wanted to monitor the job progress.

The very first version back then was a plug-in for Cura, before Cura even supported plug-ins. After my Christmas break, I went, OK, it’s doing everything I wanted it to do; back to work at my normal regular job. And then it exploded. I started getting emails, issue reports, and feature requests from all over the world. ‘Can you make it also do this?’ ‘Hey, I have this other printer with this slightly different firmware that behaves like this; can you adapt it so that it works with this?’. ‘Can you remove it from Cura, and have it so it works standalone?’ Suddenly I had this huge open-source project on my hands. I didn’t do any kind of promotion for it or anything like that. I just posted about it in a Google+ community, of all things, and from there it grew by word of mouth.

A year or so later, I reduced my regular job to 80%, to have one day a week for OctoPrint, but that didn’t suffice either with everything that was going on. Then I had the opportunity to go full-time, sponsored by a single company who also made 3D printers, and they ran out of money in 2016. That was when I turned to crowdfunding, which has been the mode of operation ever since. Around 95% of everything that is done on OctoPrint is run by me, and I work on it full-time now. Since 2014.

A lot of the stuff that I have been adding over the years, for instance, the plug-in system itself, would not have been possible as a pet side project, not with a day job.

HS: What are you working on at the moment?

GH: In March just gone, I released the next big version, to make OctoPrint Python 3-compatible, because at the start of the year Python was deemed end of life, so I had to do something. The problem is that there’s a flourishing plug-in ecosystem written in Python 2, so for now, I’m stuck with having to support both, and trying to motivate the plug-in maintainers to also migrate, which is a ton of fun actually. I wrote a migration guide, tracking in the plug-in repository how many plugs are compatible. Newly registered plug-ins have to be compatible too.

HS: Do you have any idea how many people use OctoPrint?

GH: Nine months, a year ago, I introduced usage tracking. It’s my own bundled plug-in that ships with OctoPrint that does anonymous user tracking through my own platform, so no GDPR issues should arise there. And what this shows me is that, over the course of the last seven days, I saw 66,000 instances, and the last 30 days, I saw 91,000 instances.

But that’s only those who have opted into the usage tracking, which obviously is only a fraction. I have no idea about the fraction – whether the real number is five times, ten times higher, I’ve no way of knowing.

When I did the most recent big update, I got some statistics back from piwheels [a Python package repository]. They saw a spike in repositories that were being pulled from their index, which corresponded to dependencies that the new version of OctoPrint depends on, and the spike that they saw corresponded with the day that I rolled out the new version. Based on that, it looks like there’s probably ten times as many instances out there. I didn’t expect that. So the total number of users could be 700,000, it could be over a million, I have no idea. But based on these piwheels stats, it’s in that ballpark.

HS: And are you seeing a growth in those figures?

GH: Yes. Especially now, with the pandemic going on. If you had asked me three or four months ago, just when the pandemic started, I would have told you more like 60,000 per 30 days. So I saw a significant increase. I also saw a significant usage increase in the last couple of weeks.

I also saw a significant increase in support overheads in the last couple of weeks, which was absolutely insane. It was like everyone and their mother wanted to know something from me, writing me emails, opening tickets and all that, and this influx of people has not stopped yet. At first I thought, well I’ll just go into crunch mode and weather this out, but that didn’t work out. I had to find new ways to cope in order to keep this sustainable.

HS: You can’t have crunch mode for three months!

GH: I mean it’s OK for four weeks or so, but then you start to notice side effects on your own well-being. It’s not a good idea. I’m in for the long haul.

HS: Wanting a feedback channel instead of just firing off commands that work silently makes a lot of sense.

GH: It’s not like a paper printer where you fire and forget, so treating it as a black box, where you don’t get anything back on status and all that, is bound to be trouble. This is a complicated machine where a lot of stuff can go wrong, so it makes sense to have a feedback channel — at least that was my intuition back then, and evidently, a lot of people thought the same.

HS: You must have saved people countless hours and hours of wasted time, filament, and energy.

GH: I’ve also heard that I’ve saved at least one marriage! Someone wrote me an email a couple of years ago thanking me because the person had a new printer in their garage and was constantly monitoring it, sitting in front of it. Apparently the wife and kids were not too thrilled by this. They installed OctoPrint, and since then they’ve been happy again.

Get HackSpace magazine issue 31 — out today

HackSpace magazine issue 32: on sale now!

You can read the rest of HackSpace magazine’s interview with Gina Häußge in issue 32, out today and available online from the Raspberry Pi Press online store. You can also download issue 32 for free.

The post OctoPrint: a baby monitor for your 3D printer appeared first on Raspberry Pi.

Source: Raspberry Pi – OctoPrint: a baby monitor for your 3D printer