At least the reward passes don’t expire, but that’s about the only good thing I have to say about these things

At least the reward passes don’t expire, but that’s about the only good thing I have to say about these things

Plans around the new hardware are devolving quickly

Epic is suing the leaker known as AdiraFN, who worked at the company as an associate producer

Life sims like Animal Crossing usually overwhelm me, but Pokopia has something others don’t

Ashes of Creation rapidly imploded and now the fight about why is going public

Players have high expectations for the RPG remake trilogy going into the finale

The Mario company wants its money back with interest according to a newly filed lawsuit

Nintendo’s new system may have found a system seller in the Pokémon life sim

‘Y’all got to let the numbers talk go,’ said one player to panicking Marathon fans

The Apple Immersive series Elevated reaches the Alps in its new Switzerland episode, with its narrative, visual, and audio choices giving these vantage points meaning.

Perspective in the Apple Immersive Video series Elevated is not just about altitude. It is rooted in how narrative, visual and audio choices work together to give those vantage points meaning.

The Apple Immersive Video format is 180° stereoscopic 3D video with 4K×4K per-eye resolution, 90FPS, high dynamic range (HDR), and spatial audio. It’s typically served with higher bitrate than many other immersive video platforms.

We highly praised Apple Immersive Video in our Vision Pro review. It’s not possible to cast or record Apple Immersive Video though, so you’ll have to take our word for it unless you have access to a Vision Pro.

Switzerland is the newest episode of Elevated available, following sweeping journeys over islands of Hawai’i (Episode 1) and Maine (Episode 2).

Across all three episodes of the series so far, a consistent creative approach gives each immersive episode the feeling of an authentic, elevated experience that grounds sweeping landscapes in context and perspective.

Majestic landscapes are never presented as simply beautiful and often unreachable views. Each episode carries visitors over dramatic terrain with local narrators framing these destinations as living, ever-changing environments. From landscapes shaped by powerful forces of nature in Hawai‘i to the breathtaking beauty of autumn in Maine, the episodes reinforce that our earth is alive and constantly evolving. This storytelling makes each journey over the real, visually stunning ultra-high-resolution moments captured in 180-degree stereoscopic video feel that much more precious.

Consistent Scale and Changing Perspectives

Another important creative choice of Elevated is not just the heights it reaches, but the scale it preserves. Visitors’ sense of scale in relation to these environments remains consistent and true to life, creating the sense of presence as oneself within each destination. From a small number of moments where you begin seemingly standing on the ground in Maine and Switzerland, to rising above snowcapped mountains, rugged coastlines, or dense forest – the visitor’s proportion to the landscapes holds. This has not always been the case with Apple Immersive content.

Also, while these moments on the ground are limited in the series so far, beginning at ground level before lifting into the grandeur of elevated views makes a meaningful difference. The moment in Switzerland when I’m standing at the base of mountains is now a visceral memory for me, just as much as flying over The Alps. Seeing the detail of fall leaves up close at the beginning of Maine deepened my appreciation for the vast canopy revealed moments later from above. Establishing proportion on the ground reinforces the scale that follows. The contrast is what gives the ascent weight. Elevation feels more powerful when I understand the texture, distance, and human scale of what exists below.

Movement in immersive experiences is critical to get right when its not the visitor controlling it. The speed and steadiness of the camera movement in this series offers a consistent almost ethereal quality to the pace of the flights giving visitors time to look around and absorb detail before the perspective shifts. Transitions between views also feel fluid, and not rushed or abrupt. Instead, the change in scene often feels as if perfectly timed to when visitors may have simply chosen to turn their head to look out another window into new scenery. Like previous episodes, Switzerland maintains that discipline, guiding visitors through an expansive journey across the country’s hard-to-reach terrain.

In the opening scene of Switzerland, the episode begins at ground level, allowing me to register the scale of the surrounding mountains and the quiet beauty of the ice skating path in front of me before ascent. For the first time in the series, it also experiments with introducing people into the opening scene before ascent. Two skaters enter from my right on the ice path and glide ahead in the direction I had already taken in. Instinctively, I turn to see where they came from and meet the edge of the frame of the 180-degree immersive video. In earlier episodes, I was engaged with the details of the evolving landscapes in my field of view and never felt compelled to look beyond them. Here, the entry point pulled my attention outside the designed field of view. Had the skaters entered and locked eyes with me, or stopped to playfully pick up some snow, for example, the moment could have anchored focus forward instead of prompting curiosity toward uncaptured space.

Frictionless Control Expands Moments

Epic content like this benefits from how naturally Apple Vision Pro features can be controlled. The visuals of Switzerland are so expansive and pausing to take them in with a simple gaze and pinch feels instinctive, not disruptive to the sense of immersion. My time in Switzerland felt longer than eight minutes because of that. I paused when up-close with an old castle overlooking a village. I easily found the beginning of the scene to fly right next to the Matterhorn mountain multiple times.

More of This Please

Switzerland reinforces what Elevated consistently demonstrates. Beautifully detailed visuals, compelling narrative, thoughtful pacing and preserved scale work together to create a true sense of journey. In a medium where spectacle is easy, creating the illusion of immersion is harder, especially with a limited field of view. Elevated proves that the most compelling immersive travel experiences are not only defined by where you go, but by how thoughtfully you are taken there with the best technologies available to the storytellers.

There was a time before walkthroughs

Darts VR2: Bullseye, an arcade-flavored darts game, is coming soon to all major VR platforms.

Gamitronics and Evolution Publishing have announced that Darts VR2: Bullseye is coming soon to Meta Quest, PlayStation VR2, and PC VR via Steam. The sequel to Darts VR combines classic darts games with “high-octane” modes and arcade-style gameplay, perhaps best exemplified by the game’s “Zombies” mode, described by the developers as a mode that “will test your aim under pressure as hordes of the undead come for a bite!”

A teaser trailer shows a highly stylized arcade look, with a green zombie’s hand shattering the earth, rising up to grip a flaming dartboard. It’s pretty intense.

0:00

The arcade flavor of Darts VR2: Bullseye is joined by more realistic game modes, such as 501, Around the World, and more. Online leaderboards, achievements, in-game pundit analysis, and customizable cosmetics round out the feature set.

A release date has not yet been announced, but you can wishlist Darts VR2: Bullseye now on the Meta Horizon Store, Steam, and PlayStation.

The life sim is even giving the gods of its universe a more distinct personality

I’m getting big FTX 2.0 vibes from this whole thing

AWE USA 2026 is returning to the Long Beach, CA on June 15–18. As the most important annual XR event on our calendar, we’re excited to once again be able to offer an exclusive 20% discount on tickets as the event’s Premiere Media Partner.

Since I started attending AWE USA in 2018, the conference has grown in scale and scope, offering increasingly more interesting and valuable sessions, exhibitors, and networking. It has steadily evolved into what I consider the must-go event for the XR industry. It carries the torch of passion that ignited the XR space back when it was little more than kickstarters, meetups, and those crazy enough to believe that immersive tech was not only possible to build, but worth building.

That’s why I’m proud to announce that Road to VR is once again joining AWE USA 2026 as the event’s Premiere Media Partner.

In addition to our usual reporting from the event, we’ll be highlighting the most interesting sessions and exhibitors ahead of the show, and offering an exclusive 20% discount on tickets to AWE USA 2026. Super Early Bird passes are available until March 19th—there won’t be a better deal!

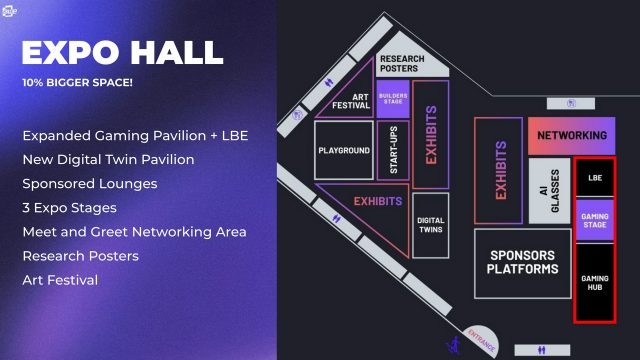

AWE USA 2026 will be held at the Long Beach Convention Center in California from June 15th to 18th, and it’s expected to draw more than 5,000 attendees, 3,250 exhibitors, 400 speakers, and feature a 150,000 sqft expo floor.

This year the conference is further growing its gaming and location-based entertainment (LBE) segments.

This year the conference is further growing its gaming and location-based entertainment (LBE) segments.

The gaming section of the show floor is not only growing to accommodate more exhibitors and attendees, but there’s a brand new LBE space dedicated to VR attractions, arcades, and activations.

Alongside the extra show floor real estate attendees can also expect a broader range of presentations and panels in the gaming & LBE track, with a full agenda coming soon. If you’re interested in featuring your game or LBE experience at AWE USA 2026, be sure to check out the upcoming webinar to learn more about the opportunities at the event.

Alongside the extra show floor real estate attendees can also expect a broader range of presentations and panels in the gaming & LBE track, with a full agenda coming soon. If you’re interested in featuring your game or LBE experience at AWE USA 2026, be sure to check out the upcoming webinar to learn more about the opportunities at the event.

The post XR’s “Must-go” Conference Expands Gaming & LBE Focus for 2026 appeared first on Road to VR.

The life sim goes out of its way to capture Pokémon’s personalities

A user saw the price of Assassin’s Creed Unity increase upon signing into their PSN account

The villain was previously leaked by a movie theater chain

The event adds the Hoppip line to your island

And yes, it deserves to be